Back on the carousel of words

The tagline reads: Around the world in 101 essays. These essays are an ‘expanded and augmented’ version of Shashi Tharoor’s World of Words column in the Khaleej Times, wherein he parses the meaning of many an English word, a term, a concept, indeed of a fast-evolving language itself.

Stray thought: this is just the book you need if you want to know where terms like ‘orange marmalade’, ‘marsification’, ‘logomisia’, or even ‘ping’ come from.

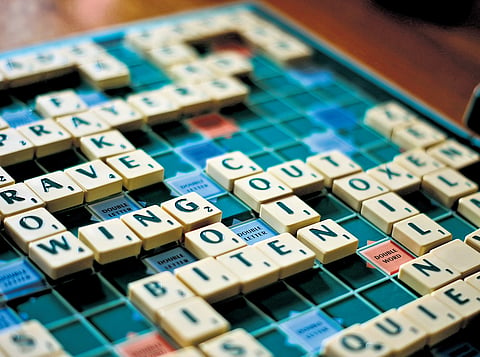

The introduction is a delight, even if it does rather tend to run on, with an engaging attempt by Tharoor at sending himself, or rather his reputation as an inexhaustible wordsmith, up. Inexplicably though, he describes Scrabble at some length, perhaps labouring under the belief that most of us wouldn’t know much about the game. Later, equally inexplicably, he sees fit to explain inflation, and goes off into a cul-de-sac explaining shrinkflation, too.

These few instances of pontification aside, the rest of the book is a fun read, and definitely an informative one, telling us about the origin of many a word. In one instance, Tharoor tells us about the word ‘ixnay’; this reviewer for one, always thought the word had sprung fully formed from the fertile brain of Plum Wodehouse. He terms his siblings and himself obstreperous, says his father was his milver, avers he’s a logophile… all of which gets the reader quickly looking up the terms!

The flashlight is swung in a wide arc. Tharoor throws light on American English and Australian English, then Irish, French, German, Japanese contributions to the Queen’s language. He smiles in understanding, even admiration, at the Indianisms we all use. In an interesting chapter, he writes of the minefield that the usage of Ukraine-specific terms have become, pointing out how language and spelling can take on distinct political overtones; why we shouldn’t be saying ‘the Ukraine’, why it’s ‘Kyiv’ not ‘Kiev’, and the meaning of the letter ‘Z’ seen on Russian tanks and military vehicles.

The passage on punctuation is one to delight all grammar Nazis, followed by those on apostrophes, hyphens and hyphenation changes through the years, which many an editor will find handy. Some chapters actually come with bulleted points for the reader in a hurry. Come to think of it, a copy of A Wonderland of Words, written by arguably India’s most well-spoken man (in English), should be a handy addition to school libraries and other educational institutions.

Elsewhere, the author takes a quick class in spelling, with its ‘across the pond’ problem to zee or not to zee, given that the UK eschews the last letter of the alphabet and substitutes ‘s’ instead in words like realise, recognise, etc. He tells us how to use vowels properly (!), educates us on pleonasms (words that combine two synonymous terms like ‘armed gunman’, ‘12 midnight’) and lethologica, which happens when we can’t recall the exact word we so badly want at a particular point in time.

He then descends into whimsy, telling us of mystifying newspaper headlines like ‘Violinist Linked to JAL Crash Blossoms’, and ‘British Left Waffles on Falklands’, which immediately took this reviewer back to her days in the newsroom and the stray howlers that would creep onto front-page headlines on a particularly busy night shift.

Tharoor rues that oftentimes the words he uses sends the reader scurrying to the dictionary, then proceeds to use words like ‘epicaricacy’ (deriving pleasure from the misfortunes of others), ‘ablaut reduplication’ (changing vowel sounds in repeated words to create new words or phrases) and ‘mundivagant’ (a life spent wandering all over the world). Now, if that isn’t classic agent provocateur behaviour, what is?

He is also savvy enough to embed sentences that subtly inform us how well his book Tharoorasaurus has done, how he got President Musharraf to laugh over a bon-mot, and yes, there are gentle linguistic digs made at lesser articulate politicians… in other countries!

There is a beautiful epigraph by Pablo Neruda (another man of letters whose day job was politics) at the start of the book: “I run after certain words…

I catch them in mid-flight, as they buzz past, I trap them, clean them, peel them, I set myself in front of the dish, they have a crystalline texture to me, vibrant, ivory, vegetable, oily, like fruit, like algae, like agates, like olives… And then I stir them, I shake them, I drink them, I gulp them down, I mash them, I garnish them… I leave them in my poem like stalactites, like slivers of polished wood, like coals, like pickings from a shipwreck, gifts from the waves… Everything exists in the word.”

Language mavens will enjoy going through this ready reckoner, with its charming jacket and neat illustrations by Priya Kuriyan kicking off every chapter. Shashi Tharoor is obviously having fun with words, and enabling the reader to do so, too.