Book review | 'A Brief History of the Present: Muslims in New India' offers critical examination of complexities

The Hindu-Muslim divide, rooted in colonial history, continues to be one of the most enduring legacies in Indian politics. In A Brief History of the Present: Muslims in New India, Hilal Ahmed, a scholar at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, offers a critical and nuanced examination of the evolving complexities of Muslim identity in today’s India.

Ahmed identifies four dominant, and often conflicting, concepts: socialism, secularism, inclusion and Hindutva-driven nationalism. These ideologies, according to Ahmed, “dominate, survive, overlap and compete with each other in the real world of politics”, shaping the doctrine of New India. The book challenges assumptions held by both liberal and conservative perspectives, employing a multifaceted methodology that seamlessly blends historical analysis, sociopolitical critique, and empirical research.

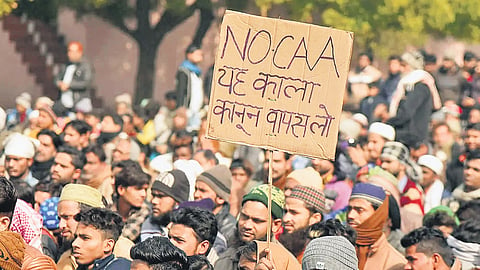

The narrative begins with a harrowing account of a tragic event on 31 July 2023, where a Railway Protection Force constable allegedly murdered four people on a train, including three Muslim passengers. Ahmed uses this incident to highlight the escalating anti-Muslim sentiment in India, where symbols of Muslim identity—such as the skull cap, beard, hijab, and even the Urdu script—are increasingly perceived as existential threats to Hinduism. This environment, Ahmed argues, has led to a dangerous rise in nationalism, where Muslims are not only marginalised but also violently targeted. He notes that the “merger between the global anti-Islamism and anti-Muslim communalism specific to India led to a new political consensus, which may be called ‘Muslim politicophobia’.”

Ahmed skilfully navigates the complex terrain of identity, resisting the reduction of Muslims to a monolithic group. He insists that researchers must maintain an objective and open-minded approach when engaging with political and social issues without losing their moral sensibilities. The book does not shy away from critiquing both ends of the political spectrum. Ahmed exposes how both proponents of Hindutva and liberal defenders of secularism have oversimplified Muslim identity—either by categorising Muslims as a homogeneous group or by failing to critically examine the power dynamics within progressive and deprived sections of society. That has provided fertile ground for the rise of Hindutva, which has capitalised on Hindu victimhood, further marginalising Muslims.

While India’s opposition parties criticise the BJP’s Hindutva narrative for distorting India’s pluralistic ethos, Ahmed extends his critique to the broader political discourse. He highlights the reluctance of non-BJP political forces to take a principled stand on Muslim identity issues, noting how the prevailing political narrative tends to pigeonhole Muslims as either a threat to Hinduism or a minority in need of protection.

In the concluding sections, the book presents four open-ended arguments. First, Ahmed calls for a reassessment of the core principles of Indian politics, including the supremacy of the Constitution, federalism and social justice. He then addresses the BJP’s internal challenges, such as its reliance on Narendra Modi as a political symbol and the marginalisation of intellectuals within the party.

Ahmed also critiques the liberal explanation of anti-Muslim violence, arguing it over emphasises the BJP’s role and overlooks deeper sociological fault lines. Finally, he highlights the role of civil society and people’s movements in shaping Indian democracy, asserting that the future depends more on civil society than electoral strategies—a view somewhat validated by the 2024 general elections. While these arguments are presented clearly and thoughtfully, they are not entirely new.

A Brief History of the Present: Muslims in New India is a compelling and thought-provoking work. Ahmed’s nuanced analysis and his deep understanding of the socio-political landscape make this book an essential read for those interested in contemporary Indian politics and the evolving dynamics of Muslim identity. The book offers a powerful critique of the prevailing narratives that continue to shape the lives of millions of Muslims in India today.