The deeply patriarchal society we live in is nothing short of a dystopia for women—more so for Dalit women. A woman is never free from scrutiny; she lives under constant surveillance, much like contestants trapped inside the sets of a Bigg Boss reality show.

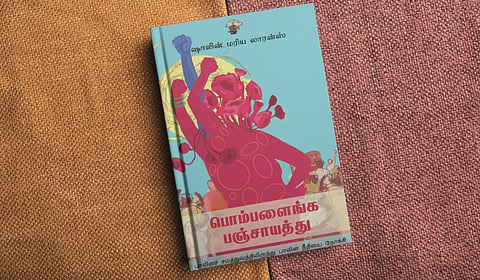

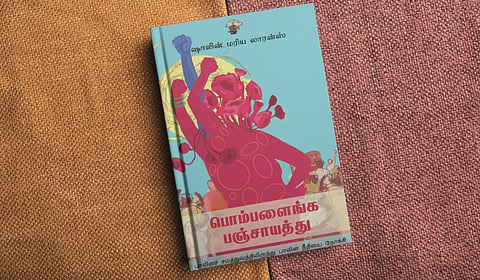

In Pombalainga Panchayat (Women’s Panchayat or Council), published by Kalachuvadu, Shalin Maria Lawrence breathes fire against misogyny and caste hegemony. In her fierce yet humorous rants, she mocks and abuses men—yes, all men. This rage is political; it emerges from lived experience and sustained injustice. Love it or not, it's no-holds-barred male bashing that's on offer.

A slim volume of thirty essays written in Tamil, the book carries the tagline From 'Gender Equality to Gender Justice'. Across these essays, Shalin launches an unflinching assault on patriarchy while never entirely losing her sense of humour.

In one essay, she writes: “The bra is not a TMT bar meant to cover everything. Scientifically, it is meant to relieve chest and back pain. If the strap of a bra protruding from a blouse is a problem for men, for me the bra itself is the problem.”

This sharp observation lays bare the absurdity of men constantly dictating what women should or should not wear. As Shalin makes clear, the problem is not women’s clothing, but the gaze of the beholder—and the rot in a society that justifies that gaze.

On the dowry system, she remarks with brutal irony that India may be the only country to have fixed a price for the male genital organ—without shame or embarrassment. For men, she argues, women are expected to sleep with them, bear their children, care for them, and still look like Deepika Padukone.

What, then, is the cure for this affliction? Feminism? But Shalin pushes the conversation further—beyond feminism toward gender justice.

Her essays traverse caste and class hegemony, gender inequality, and political hypocrisy. She criticises the move to increase the minimum marriage age for women from 18 to 21, interrogates jallikattu as a celebration of toxic masculinity, and skewers cinematic representations of love—from T Rajendar’s films to those of his son, Simbu.

Shalin also dismantles the myth of Tamil Nadu as a progressive utopia. The state, often projected as Periyar’s land, leads the country in the number of deaths of Dalit sanitation workers. Caste-based crimes remain alarmingly high, and violence against Dalit women has reportedly increased by 40 percent in the last two years.

“Just as there are two Indias,” she writes, “there are two Tamil Nadus”—one inhabited by Dalits facing everyday violence and exclusion, and another carefully curated as a social paradise. Untouchability, she notes, is practised in over 40,000 villages in the state.

In another essay, Shalin examines the position of women in the police force. The first batch of women police officers in Tamil Nadu was inducted in 1972—a move seen as revolutionary at the time. Four decades later, women make up 18 percent of the force, a significant figure by Indian standards. Yet most remain constables, working in a system never designed to include them. Even their uniforms, she notes, were designed for men. She pointedly asks why society extends more respect to an imaginary character like Vyjayanthi IPS than to real women police constables. In school functions, girls playing police officers were once made to wear moustaches along with the uniform—a telling symbol of how authority itself is imagined as male.

“Truth hurts. I am also hurt,” she writes—perhaps the most honest line in the book.

Recalling a meeting of Congress leaders following Rahul Gandhi’s Bharat Jodo Yatra, Shalin writes about the uneasy silence that followed her statement:

“Dr Ambedkar said the progress of a society is measured by the degree of progress achieved by women. But for me, the true measure of social progress lies in the advancement of Dalit women.”

In the book’s preview, she describes Pombalainga Panchayat not merely as a collection of essays, but as a testimony to silenced voices, ignored struggles, and uncelebrated talents. She frames the book as an invitation—especially to men in positions of power—to engage in self-reflection. The work is both a tribute to Dr BR Ambedkar, whom she regards as the only leader among his contemporaries to be a true feminist, and a dedication to the countless women leaders who continue their struggles while being pushed to the margins of life.

Shalin Maria Lawrence, who has a loud presence on social media, with her legitimate rage, writes from practical wisdom and lived experience. She makes sweeping statements, yes—but they are born of structural violence, not casual prejudice. She busts myths, debunks stereotypes...Pombalainga Panchayat may unsettle, provoke, and anger its readers, but it serves as a necessary eye-opener for men—certainly for men like me.