Is what you see and what you think you see two different things? The ancient Greeks did think so. The Greco-Roman ruin of the Library of Celsus in Turkey, commissioned in 110 AD, is one of the most prominent buildings boasting an optical illusion. Built on a narrow ledge, it gives the illusion of a grand structure. The supporting columns—not aligned on purpose—convey an impression of a larger façade than the actual one. Closer home, the 900-year-old Airavatesvara temple located in Kumbakonam in Thanjavur district of Tamil Nadu is one of the oldest cases of such an optical illusion. It was built by Rajaraja Chola II, and added to the UNESCO World Heritage Site list of Great Living Chola Temples in 2004.

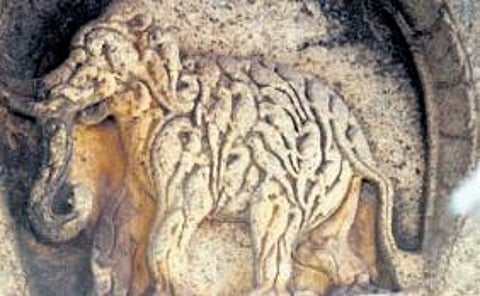

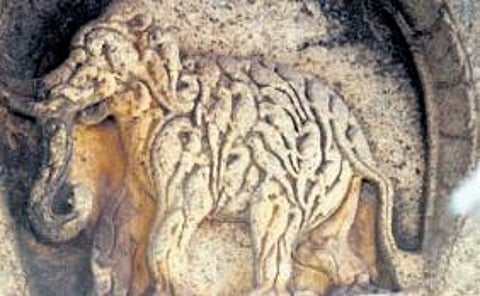

The entire temple is architecturally impressive, with the rishabha-kunjara (bull and elephant in Sanskrit) carving standing out. The masterful sculpture has the body of the two animals skillfully overlapping. If you stand on the left of it, which has a bull, and cover the lower part of the carving, you can clearly see an elephant, with its eyes and a curved, upturned trunk.

On moving to the right and covering the elephant, you can see a bull with its eyes and nostrils and hump, all raised upwards, looking skywards as it were. The elephant’s trunk becomes the hump of the bull; and the horns and ears of the bull become the snout of the elephant, depending on which side you are looking from and which part you are obscuring from vision. The proportions of both animals are matched impeccably to create the perfect optical illusion.

The bull is the vehicle of Shiva and the elephant is the favoured animal of Vishnu’s consort Lakshmi (as well as of Indra whose mount is the Airavat, or white elephant). Thus, the idea was to show, symbolically, that both Shiva and Vishnu are the same. It is significant since these were times of deep differences (which endured for several centuries) between the followers of both gods and their respective faiths—Shaivism and Vaishnavism.

Sivasankar Babu, Heritage Awareness Speaker, Tamil Heritage Trust, explains, “The rishabha-kunjara is a syncretic sculpture. It signifies the common path and unity of Shiva and Vishnu margas by uniting Shiva’s vahana (vehicle) with Lakshmi’s.

There are two variations in the use of the bull and elephant. The Airavateswara shows the bull on the left and the elephant on the right. In other place, the elephant is on the left and the bull on the right, for instance, at the 13th-century Kampahareshwara temple in Thirubhuvanam. In fact, this rishabha-kunjara (or its converse) sculpture is seen consistently in the temples built from 10th century onwards to the 17th century in several Vijayanagara and Chola sites, and also Chettiar-period temple constructions from 18th to 20th century AD. Also, the complexity keeps increasing with more elements being added.”

To illustrate his point, he refers to the Kapaleshwara temple, in Mylapore, Chennai where you can see a stucco image of a kunjara-rishabha with Lakshmi and Vishnu, and Shiva and Parvathi atop their respective vahanas on the gopuram. Babu, however, feels among the best examples are the miniature sculptures of the 17th-century Thirukurungudi temple, Thirunelveli, Tamil Nadu—a horse made of parrots; sapthanari ashva (horse made of seven female forms); elephant made of parrots; and the navanari kunjara (elephant made of nine female forms).

There are also sculptures of four monkeys with one common head and four women with one common head. Harihareshwara temple in Harihar, Karnataka, has Krishna with five bodies; each body when seen in isolation appears complete. At Lepakshi temple in Andhra Pradesh, there is a figure of an animal with one body, but three heads facing in different directions, each of which seems complete when seen in isolation. The Hazara Rama temple at Hampi, Karnataka, has what appears to be a four-legged person depicting three dancers sporting a variety of mudras.

Paintings are another medium where artists have showcased their talent in creating optical illusions. A well-known example is Ukranian artist Oleg Shuplyak’s painting of Dutch master of Vincent van Gogh. Back home, our own Raja Ravi Varma also painted a kunjara-rishabha optical illusion with the kunjara (elephant) on the left carrying Vishnu and Lakshmi, and rishabha (bull) on the right carrying Shiva and Parvathi with their son Ganesha. Several old and new Tanjore paintings contain the motif as an optical illusion.

Many such sculptures are waiting to be discovered around India in centuries-old temples, all of which would speak of the unparalleled skills of our artists.

WHAT IS OPTICAL ILLUSION

These are images that play with our eyes and minds and create layers of images in one. They are about intelligent, skilful art as well as visual trickery. In modern times, psychologists use it to detect personality traits or attitudes and even levels of intelligence. They employ it to identify persons as right-brained or left-brained.