A preoccupation with gods and goddesses is an Indian trademark, no matter one’s religious affiliation. When it comes to tantric Yogini goddesses, the interest, however, is not limited to Indians. Swiss-Panamanian writer Stella Dupuis first felt their call when she visited the Hirapur Yogini Temple in Odisha. Not much had been documented on these mostly local village divinities, but a deep search led her to two books—Yogini Cult and Temples by Dr Vidya Dehejia, and Les Enseignements Iconographiques de L’Agni Purana by Dr Mari-Thérése de Mallmann—both of which shared locations of several neglected temple sites.

Fascinated, Dupuis began visiting them and compiled a comprehensive guide book. Over the years, she has written several articles and books in different languages, designed oracle cards on a Yogini theme and established a sort of shrine to these powerful beings in the small town of Villa de Leyva in Colombia. The latest addition to her Yogini repertoire is Experiencing the Goddess: On the Trail of the Yoginis, a collection of essays edited by her and launched at this year’s Jaipur Literature Festival.

Popularly known as the ‘Chausatha’ or sixty-four Yoginis, even though documented numbers vary from eight to eighty-one, these set of goddesses are preserved as sculptures in temples across India, dating as far back as the 6th to 7th centuries CE. Though worshipped in various forms, collectively they signify Shakti or the female energy to which all creation is attributed. Many of their temples are found near capitals of erstwhile ruling dynasties, suggesting their worship by kings for protection against enemies or to prevent public calamities such as epidemics, floods or droughts.

After the 12th century, evidence suggests a waning of their appeal, leading to neglect and disfiguration of their sculptures and sites of worship. Dr Dehejia’s extensive travels and documentation of these sites in the 1980s led to a resurgence in interest. Though the voluptuous Yoginis are represented differently throughout India—both in human and anthropomorphic forms—there are striking similarities in the temple constructions. The shrines are usually roofless and circular enclosures unlike most Indian temples.

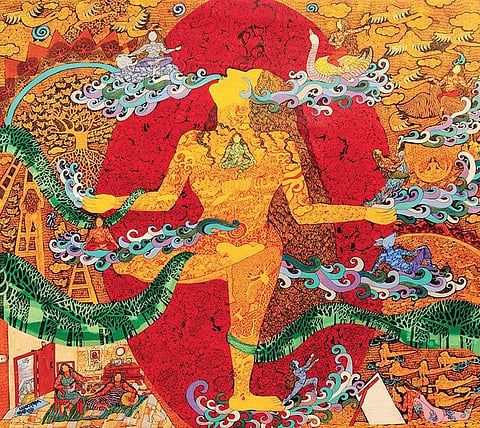

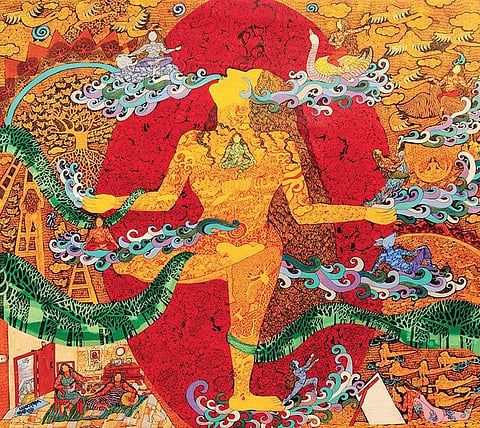

Multi-disciplinary artist Seema Kohli’s interest in the concept of energy or Shakti manifested in the Yogini form being a recurrent theme in her striking works of art. Her piece in the book recreates her divine experience through images and words. “The visual manifestation of the goddess helps in explaining this esoteric concept to the viewer. After all, history is best examined through the artistic works of the time,” she says.

The Yoginis have traditionally been worshipped both as benevolent beings and malevolent punishers. In her essay, American researcher and director of Matrika Charitable Trust, Janet Chawla, captures this aspect of ambivalence that connects Yoginis to traditional Indian birth goddesses. “These deities swing both ways—they can bless you or curse you and therefore have a similar effect on their devotees,” she says. Having travelled extensively through India documenting birth practices—especially the rituals of local dais or midwives—Chawla recounts the power of these spiritual beings on locals.

Apart from the esoteric and experiential, the book also offers an academic perspective of the Yoginis. Dr Nilima Chitgopekar, Associate Professor of History at Delhi University, has extensively researched on Yogini temples. In her contribution to the book, she seeks to establish the presence of the Yoginis in ancient religious scriptures, particularly the ‘Lalita Sahasranama’ from the Brahmanda Purana. The historical and factual framework she provides is further enhanced by the scholarly outlook of Anamika Roy, Art Historian and Professor at the University of Allahabad. Her detailed explanation of the Vamadeva and Shahdol Yogini images in her essay provides interesting insight on the imagery of the goddesses.

Despite her grounding in academia, Roy states her connection to the goddesses is from within. She feels that the Yoginis guide her in every stage of her work, often pushing and sometimes holding her progress back. “The work on my earlier book Sixty-Four Yoginis was taking very long. An old professor told me that it will be completed only when the Yoginis are pleased with it,” she states emphatically.

The Yoginis have brought these women from diverse vocations together—both literally and figuratively. After extensive travel and weekly discussions on the subject, the contributors of Experiencing the Goddess: On the Trail of the Yoginis feel a special connection with each other, manifest aptly in this book. This sisterhood clearly expands beyond borders—as does the charm of the Yoginis.