Awaiting a golden moment

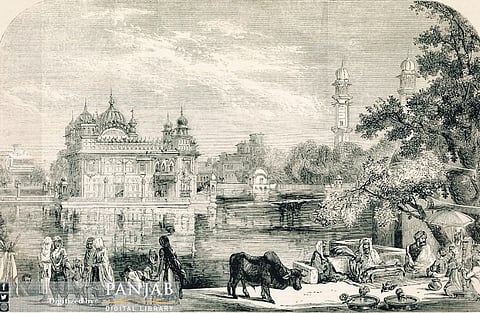

A drawing of the Durbar Sahib in Amritsar by William Carpenter in 1840 shows the Golden Temple as a towering structure with minarets rising through tree tops beside the placid waters of the Amrit Sarovar which was built by Guru Ram Das. In the drawing, a bunch of women walk alongside the sarovar and a big black bull ambles towards two urns.

A lithograph shows the temple in its intricately carved glory, and a boatman on a small canoe hopefully looking at a couple of turbanned Sikhs. Amritsar then was an idyllic town, uncluttered by shoulder to shoulder shops selling jootis and temple merchandise, meshes of low lying electric lines and the clutter of a million pilgrims.

The jewel in Punjab’s crown is without doubt the Golden Temple, the highest seat of Sikh faith. Like all Indian temple cities especially in the North, Amritsar is no longer the pastoral experience that inspired the fourth Guru. It is a sprawling ugly urban mess whose chole kulcha is a fave trademark even as the 400-year-old city’s crumbling brick buildings, elaborate frescos, ornate doors and the colonial age Town Hall mourn a lost time. While on a heritage walk around the old bazars, one can visualise Guru Ramdass’ shopkeepers working hard to make a new city, then called Ramdaspur.

In 1765, Jassa Singh Ahluwalia defeated Afghan invader Ahmad Shah Abdali in the Battle of Amritsar and established the Katra Ahluwalia, a self-sufficient, small neighbourhood. “Such neighbourhoods were a common feature in the city,” says heritage architect Gurmeet Rai. Like the Har Mandir Sahib and the other sarovars of Amritsar, the katras were also made of the Nanakshahi bricks—thin, long, red blocks mostly found in Amritsar and Lahore; and named after Guru Nanak.

Ahluwalia also constructed the Ahluwalia fort to safeguard his katra. The divine, however, is ever-present here; the Udasin Ashram Akhara Sanglawala, founded in 1771 remains a place for ascetics to meditate. The slow march of change eventually led from the idyll to commerce; in the 1900s, Marwari businessmen transformed the fort into a residence-cum-business precinct. “Their gaddis (seats) and shops were placed in the front of the building and residences were at the back and on the upper floors,” says Balvinder Singh, former architecture professor of Guru Nanak Devv University.

Amritsar’s built heritage is the last remnant of the city’s eventful past, holding its ground amid the chaos of haggling tourists, cycle rickshaw bells and the smell of fried snacks. “It’s fascinating to see the many narratives of Amritsar; of the Afghans, Sikhs and English in the city’s old buildings,” says Rai, who worked on restoring the Golden Temple on the now revamped Heritage Street.

Martyrdom is part of Amritsar’s legacy. The Gurudwara Saragarhi is dedicated to the 21 soldiers of the 36 Sikhs Battalion who lost their lives on September 12, 1897, protecting Fort Lockhart in Saragarhi (now in Pakistan), against 10,000 Pathan tribesmen. One of the three gurudwaras built to commemorate their sacrifice is in Amritsar in 1902.

But the buildings of the old bazars are crumbling. So are the brick buildings around katra structures. “Restoration must become part of the urban fabric; only then can heritage and the stories they hold survive,” says Rai. For the Sikh community, which is proud of its heritage and giving back could step up and help restore the legacy of Guru Ramdass. Ambersar then can live as the city of gold, not of old, lost memories.