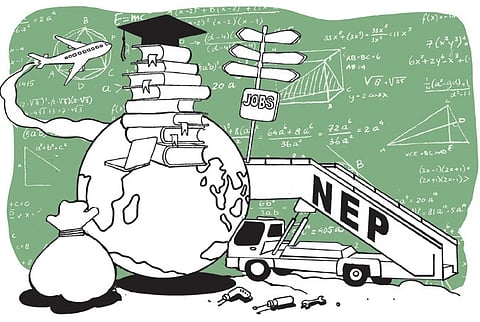

Improve ground-level application of NEP

During the last two years there has been a flurry of activity at the level of several national agencies that oversee higher education and also at the level of individual institutions vis-a-vis the implementation of the National Education Policy (NEP), 2020. Altogether, the policy has been around now for four years and perhaps the time has come to assess—in a preliminary manner—its state at the ground level. If one were to undertake such an exercise what exactly would we need to look for to draw a reasonable picture of the status of implementation of the NEP?

Perhaps, the best way to answer this is to see if the outcomes that the NEP expects from its implementation have begun to manifest themselves at the ground level. Since I am a mathematician, it comes easily for me to look at the ground-level manifestation of the NEP that is centred around mathematics. To begin with, we must not lose sight of the fact that the NEP essentially rests on four principles; its pedagogy urges significant stress on problem-solving in real-world situations through group-based projects while relying on a transdisciplinary approach.

It also urges that the curriculum should be centered around the needs and challenges of society and of the nation. Finally, it stresses that we need to pare the content. The NEP also stresses that universities must ensure that students acquire certain essential skills through the process of acquiring knowledge. What skills would a mathematics undergraduate be expected to acquire? To my mind, the mathematics student at the end of four years should be proficient in the basic streams that constitute a mathematics foundation but with the proviso that the student sees the area in the context of an application if she so chooses.

If not, then she can move ahead in a more pure sense as she advances into the final two years. The course structure must bear in mind that the number of students who opt for learning the purer aspects of mathematics are very few when compared with those students who wish to see mathematics in action. At the same time the student should have become proficient in her communication and language skills as well in the matter of IT, coding and algorithms as well as a certain facility with the handling of data and in working in groups and formulating problems.

Several universities have instituted strange course titles under the garb of what they tout as “value addition”. I wonder if the other courses cause devaluation. However, the most worrying aspect of the entire course structure is that the student ends up being heavily burdened in terms of time due to the large number of credit courses. I doubt if the student shall have any time to truly think and be creative through some interesting projects. Just as worrying is the absence of any material to convey to the student that she has acquired a specialisation in some interesting area that shall lead her to a fulfilling job.

Contrast this with the manner in which a leading university abroad explains to its mathematics undergraduate students that they can expect through a mathematics first degree to become a cybersecurity analyst, sports statistician, journalist, games designer, biomedical researcher, metrologist, IT specialist, finance expert, teacher and so on. This is in addition to becoming a research mathematician. We need to do some significant rethinking at the ground level to ensure that our student is better served by the true value of the NEP.

Dinesh Singh

Former Vice-Chancellor, Delhi University; Adjunct Professor of Mathematics, University of Houston, US

Posts on X: @DineshSinghEDU