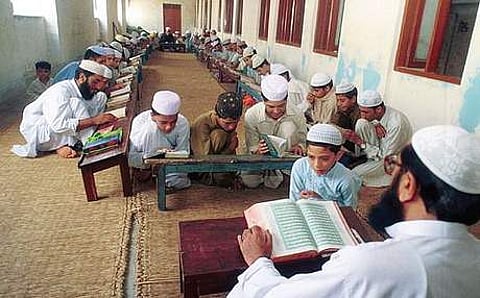

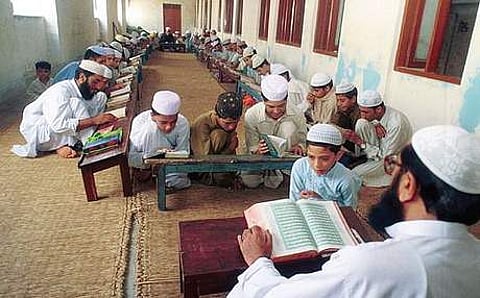

NEW DELHI: The National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) has filed its written submissions in the Supreme Court and expressed serious concerns about the kind of education imparted through madrasas.

"In the interest of the children, we humbly submit that the education imparted to children in madrasas is not comprehensive, and is therefore against the provisions of Right to Education (RTE) Act, 2009," the NCPCR said in its affidavit filed before the top court.

The NCPCR filed its affidavit in the case pertaining to the Allahabad High Court's decision striking down the 'Uttar Pradesh Board of Madrasa Education Act 2004'.

In April, the Supreme Court had stayed the HC's judgment, saying it prima facie misconstrued the Act and that the decision would impact nearly 17 lakh students.

"The denial to extend right to education to children by these institutions with minority status not just deprives the children of their most important fundamental right to education. This exclusion/denial of these children snowballs into depriving them of their fundamental right to equality before law (Article 14); prohibition of discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth (Article 15(1))," the NCPCR said.

It further said that the Act, instead of being an enabling tool, has become a depriving tool for children studying in minority institutions. In addition, such institutes are also providing Islamic religious education to non-Muslims which is further in violation of Article 28 (3) of the Constitution of India.

The NCPCR said that most madrasas face several issues in ensuring quality education to the children: it said that they fail to provide a holistic environment to students, including planning social events, or extracurricular activities for 'experiential learning'. It also said children are majorly given religious teachings "with very little participation in the national mainstream education system" and the teachers appointed are by the individual management of madrasas "failing to uphold the standards laid down under the Schedule of RTE Act (Right To Education Act) stating the Norms and Standards for a school". Children are also deprived of other basic amenities and the environment of formal education.

Commenting on the Allahabad HC's March 22 verdict, a three-judge bench of the top court, headed by the Chief Justice of India (CJI) D Y Chandrachud, had in April this year pointed out that the finding of the HC that the establishment of a madrassa board prima facie seemed to breach the principles of secularism may not be correct. It said it would examine the pleas later in a detailed manner in July.

The order of the top court seemed to bring a major relief for as many as 16 lakh students studying across around 16,000 madrasas in Uttar Pradesh.

The apex court passed the order after hearing a batch of appeals filed against the HC order by Anjum Kadari, Managers Association Madaris Arabiya (UP), All India Teachers Association Madaris Arabiya (New Delhi) and others.

“The object and purpose of the madrasa board is regulatory in nature and Allahabad High Court is not prima facie correct that establishment of the board will breach secularism. It (High Court judgement) conflates madrasa education with the regulatory powers entrusted with the Board. The judgment shall remain stayed," the top court said in its order on April.

The HC had in July in its verdict held that the 2004 law was "unconstitutional" for violating the principle of secularism and directed the government to accommodate all madrasa students in the formal education system.

On hearing the batch of appeals, the top court today also issued notice to the Uttar Pradesh government and asked it to file its detailed reply.

It also in its order observed that the HC appeared to have misconstrued the provisions of the Madrasa Act, since it does not provide only for religious instruction.

The apex court, while taking a student centric approach, observed that if the concern in this case was to ensure that students of madrasas receive quality education, then the remedy would not lie in striking down the Madrasa Act but in issuing suitable directions to ensure that the students are not deprived of quality education.

Senior advocate Abhishek Manu Singhvi, appearing for one of the petitioners, told the SC that madrasas existed for more than 120 years, and if it would now be disrupted suddenly, then it would badly affect 17 lakh students and 10,000 teachers.

Singhvi also pointed out to the SC that it would be very difficult to adjust these students and teachers to the state education system abruptly.