Duvvuri Subbarao, topper of the 1972 IAS batch, has written his memoir, Just a Mercenary? When I presented my memoir to Kerala Governor Arif Mohammed Khan, he said, “For reconstructing the history of a country during a particular period, memoirs are of exceptional value because they record the views of the actual people who played roles in the drama as it evolved.” Indian history owes much to travellers who journeyed across the country and recorded in painstaking detail its social life in different parts and their reflections on the rulers and courts they came across. We also owe much to the memoirs of rulers such as Babar and Jahangir.

I have not read Subbarao’s book, but I read interviews about it. As attention can be captured more through denigration of people in power, particularly civil servants, these interviews are also confined to running down the IAS. Subbarao was an outstanding officer whose merit was rewarded by successive governments. Rarely do officers become Union finance secretary and then be chosen as RBI governor. In my memoir, I recalled with gratitude the sterling role he played for India during the Great Recession of 2008-9. I wrote, “For India, the answer lay in the Government of India and the Reserve Bank, then led by D Subbarao, acting in sync.”

Subbarao also acknowledges the country has been fair to him and recognised his worth. In the concluding portion, he writes, “We are all prone to complaining about our country—how it is unfair, unjust and unequal. I complain too. But when I look back on my life and career without any bias, I realise that this country has given me so much...warts and all, there are still opportunities for merit in our country.”

I was, therefore, more than a little surprised at some answers he gave to a periodical. He reportedly said, “About 25 percent of IAS officers are either corrupt or incompetent. The middle 50 percent started well, but have become complacent while only the top 25 percent are truly delivering.” His reform suggestion? “I suggest a two-level entry system: initial entry for those aged 25-35, and a second tier for individuals aged 37-45. This isn’t about lateral entry, but bringing in professionals from diverse fields like journalism, engineering, medicine, NGOs, entrepreneurship and farming. Those who enter young should be evaluated after 15 years, with one-third being replaced by fresh entrants.”

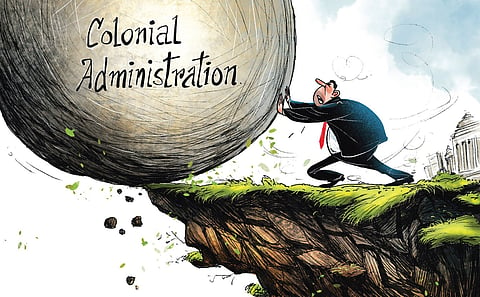

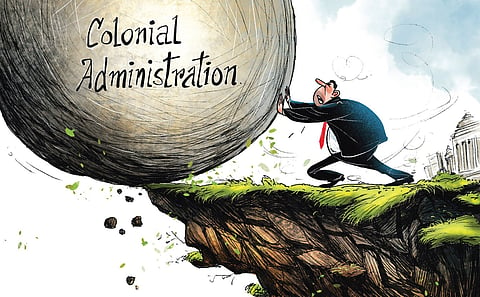

Regarding the first part of the quote, I have read elsewhere that this formula of 25:50:25 was not Subbarao’s creation but what a former chief minister told him. The fact is that comparing the ICS and early IAS officers with subsequent ones is like comparing apples with oranges. The early officers were working under a colonial political system where the sole objectives were accumulating revenue for the parent country and maintaining peace in the land. This regime continued for some years in independent India, too, until the compulsions of the new democratic political system built a new power equation with elected legislators being perceived as a bridge between the people and the government.

Over the years, the civil service had to reinvent itself to take on board the realities of the new situation. This political reality became even more accentuated with the slow but inevitable evolution of the Panchayati Raj system. It is highly creditable that the civil services, particularly the IAS, adjusted well to the new political regime and still achieved significant results using leaders of the same political structure.

I also have concerns about the new reforms suggested by Subbarao. These are premised on the assumption that administration and the quality of administrators have declined because there is something wrong with the individuals who constitute these services. These new entrants come from the same stock as the ones before or those who go into other sectors of the economy. There are MBAs, doctors, engineers, IIT graduates, people who have worked in the corporate sector, all coming into the IAS and other civil services after battling through a difficult examination, which is far more competitive than in the years in which Subbarao and I entered the IAS. There is immense potential for harnessing their skills and building a powerful administrative system, making India a developed country long before 2047.

The fact is there is nothing wrong with the officers constituting the system but with the system itself. While the political system has changed, the administrative system is the same. S K Das, in his excellent book, Building a World Class Civil Service for Twenty-First Century India, writes, “David Potter, professor of political science at Open University, UK, wrote an interesting book called India’s Political Administrator: From ICS to IAS in 1998. Potter came to the conclusion that the central features of the ICS tradition of administration continued in independent India. According to him, ‘The content of the ICS tradition was not only the concern of the IAS men and women within it, for it has influenced the behaviour of the other administrators and affected the general character of the Indian state structure as a whole.’ Potter found that, ‘Although much had changed by the early 1980s, this basic framework of administration was still in place.’ “

The system needs to undergo a sea change, shifting from the present process-oriented framework to an outcome-oriented system, with outcomes being defined as actual benefits to the people in areas where they want improvement. Public administration is entirely different from corporate governance; its goals are diverse, straddling multiple sectors, and they change from time to time as governments change. State governments’ priorities may differ from the Centre’s. Civil servants in India have learnt to adapt themselves to change. Changing these experienced officers is no solution to the problem of governance.

The words “steel frame” are no longer relevant. The present-day officer cannot achieve results if he is inflexible. Many countries, including our erstwhile political masters, the UK, have swept away old process-oriented systems and created new outcome-based systems. We have also tried—with performance budgeting, outcome budgeting and results framework documents at different times. We failed to make headway on account of lack of consistency and insufficient political ownership.

I hope that whichever formation comes to power this June prioritises overhauling the administrative system, making it an outcome-oriented one, with the PM and the Cabinet themselves steering it.

(Views are personal)

(kmchandrasekhar@gmail.com)

K M Chandrasekhar | Former Cabinet Secretary and author of As Good as My Word: A Memoir