As January 22 approaches, an unprecedented fervour grips the nation as we prepare for the inauguration of the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya. While all the competitive politics surrounding it, especially in an election year, is inevitable and also insignificant for several of us, a confident expression of hope and faith for a multitude of common Indians who have no overt political or ideological tilts is unmissable.

It is truly an epochal moment when the soul of a civilisation long suppressed seems to be finally finding utterance—75 years after the nation found that voice. Mass prayers and lighting of lamps across temples in cities and villages, marathon chanting sprees, people placing earthen lamps in front of their homes to commemorate the return of Ram from his exile—everyone being that proverbial squirrel that did its tiny bit in building Ram’s ambitious bridge to Lanka.

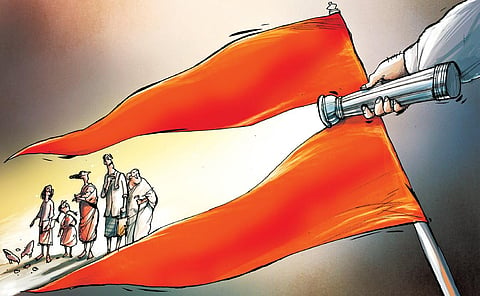

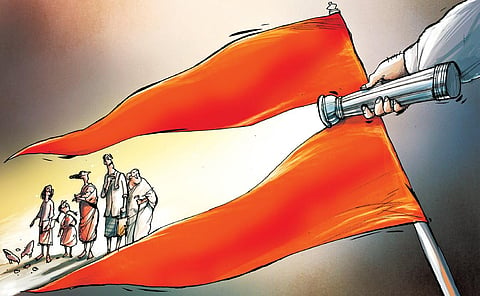

For the longest time, a Hindu was called upon to look at herself with sheer apologia, and made to believe that we were a rootless civilisation that ran merely on a sterile codification of laws. Every other community in India could proudly wear its identity and faith on their sleeve. But for a Hindu to do so was deemed regressive and communal.

Hindus are hammered with hysterical harangues of them having a disaggregated faith that did not believe in congregation—their teerth yatras and shahi snaans notwithstanding. Hence their expression of their faith had to be muted. After all, making the minorities comfortable was the only goal of Indian secularism as was perversely practiced. This belief has received a massive jolt with the upcoming inauguration.

Much is known now about the history of the Ayodhya case itself. It is a testimony of 500 years of dogged resilience that Hindus showed to reclaim one of their holiest spaces. Foreign travellers and British administrators, from William Finch, Thomas Herbert, Joseph Tieffenthaler, Robert Montgomery Martin and several others recounted how, despite its destruction by Babar, the shrine received the quiet adoration of devout Hindus.

From the efforts of the Marathas and Nihang Sikhs to numerous litigations that went on in British courts since 1858, the desire to consecrate a grand Ram temple here is not a recent phenomenon. The wealth of literary, historical and legal proofs, as also archaeological evidence that emerged through the Archaeological Survey adds further credence. That it was always called Masjid-e-Janamsthan and not Babri Masjid was a further giveaway as to whose birthplace it was commemorating.

Yet Hindus had to wait patiently for five centuries and, even after freedom, go through tortuous legal processes to get back what was rightfully theirs. Today, when that cherished dream is being realised, we are asked not to celebrate it too much. In a way, the Ayodhya consecration demolishes for good this very warped Nehruvian idea of India where the ancient had to be eased out and replaced with a new India that had a tenuous connection with its past at best.

The Somnath flashpoint was a case in point where Nehru frowned on the exercise as being Hindu-revivalist and one that would affect his government’s secular image abroad. He even prevailed upon President Rajendra Prasad not to participate in the inauguration. Nehru would have rather restored and given the temple away to the ASI than reinstall the jyotirlinga.

The past was good to be appreciated as a fossilised museum piece, but never as a living tradition. Consequently, Hindu holy sites, especially in North India—be it Ayodhya, Kashi, Vrindavan, Prayag, Gaya or Mathura—languished in utter squalor with no significant infrastructure, sanitation or tourism facilities.

The biggest irony is that the same ‘secular’ state has no qualms in controlling only Hindu temples and educational institutions. Governments of just 10 states control more than 110,000 temples, with the Tamil Nadu temple trusts owning 478,000 acres of temple land and controlling 36,425 temples and 56 mutts. All other minority institutions have the rights to own and manage their religious and educational institutions in a secular India. Draconian laws like the Places of Worship Act of 1991 prevents Hindus from even seeking peaceful, legal reclaim of what has been forcibly snatched from them. Which justice-abiding democracy in the world would have such provisions?

Even in Muslim countries, mosques are routinely displaced for mundane needs like widening roads or laying railway lines. But in India, the albatross of secularism always rests on Hindu shoulders. Appropriating the resources of Hindu institutions does not compromise constitutional moralities, but the prime minister inaugurating an iconic temple shatters the ever-fragile warp and weft of our secularism.

The Ayodhya inauguration is also a blow to the pernicious role played by ideologically-driven historians who blatantly lied in court and got away with no repercussions. As K K Muhammad, former regional director (north) of ASI, who was part of the Ayodhya survey, reveals that these dubious historians brainwashed the Muslim community, which was conciliatory initially, and instilled false hopes that they would manufacture evidence in their favour.

Unsubstantiated propaganda was passed off as history in several cases, including Kashi Vishwanath, by Congressmen such as Pattabhi Sitaramayya or Bishambhar Nath Pande. Marxist historians such as Gargi Chakravartty and K N Panikkar claimed Aurangzeb destroyed the temple not of his own will, but on the advice of Hindu rajas who were outraged by priests molesting the Rani of Kutch. Demonise the Brahmin, undermine Hindu faith, whitewash and act as apologists for Islamic bigots was a clear pattern of Nehruvian secular historiography. This stands delegitimised today.

For a meta-civilisational hero like Ram, who inspires adulation and reverence across nations, be it Vietnam, Indonesia, Philippines, Cambodia or Thailand; where art forms, murals, dance dramas are inspired by his life story, to not have a grand temple at his believed birthplace was a national shame. This is being rectified now.

At the height of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement, V S Naipaul saw it as “a new, historical awakening” of “Indians becoming alive to their history” and “beginning to understand that there has been a great vandalising of India”. On this momentous occasion, when Ram returns to his birth town from a 500-year exile, commentators looking at this in juvenile binaries of temple versus employment or BJP vs non-BJP are infantilising this genuine civilisational renaissance. India has long slipped from the iron fists of Nehruvians and their assorted elite clubs of courtiers. To wake up to this reality will do them all a tonne of good.

Vikram Sampat, Historian, fellow of the Royal Historical Society, author of 8 books including the upcoming Waiting for Shiva: Unearthing the Truth of Kashi’s Gyan Vapi

(Views are personal)