The Supreme Court recently dismissed a petition filed by one G Venkiteswarlu who alleged that his brain was being controlled by other persons through a machine. The petitioner had initially filed a writ petition in the Andhra Pradesh High Court claiming that certain persons had obtained a "human brain reading machinery" from the Central Forensic Scientific Laboratory (CFSL), Hyderabad, and used the same on the petitioner. He sought directions from the Court to deactivate the machine.

The CFSL filed a counter-affidavit in the High Court stating that there was never any forensic examination conducted on the petitioner at any point of time and hence the question of deactivation of the machine alleged to have been used on the petitioner did not arise.

Challenging the High Court's judgment, Venkiteswarlu filed a Special Leave Petition in the Supreme Court. On September 27, 2024, the Supreme Court, instead of dismissing the bizarre petition straightaway, directed the Supreme Court Legal Services Committee to arrange an interaction with the petitioner to understand his actual grievances.

After interacting with the petitioner, the SCLSC submitted to the Court that the petitioner wanted deactivation of the alleged device which was controlling his brain. "We see no scope or reason as to how we can interfere in this matter," the Supreme Court observed while dismissing the petition.

The Supreme Court's magnanimity to admit and hear the petition, despite it being prima facie bizarre, demonstrates the Court's serious concern over the liberty of thought.

Neurons under siege

In 1890, when future American Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis was thirty-four years old, he worried about the "numerous mechanical devices" that would soon allow "what is whispered in the closet" to be "proclaimed from the house-tops". He and his law partner Samuel Warren were so concerned about the implications of these advances that they penned a groundbreaking essay that argued for a legal right to privacy.

While Brandeis and Warren couldn't have anticipated governments' use of neural data, they nevertheless argued for the protection of our "thoughts, sentiments and emotions".

In light of Louis Brandeis' prescient views, we cannot simply dismiss Venkiteswarlu's apprehensions as a wild paranoic imagination of a psychotic mind.

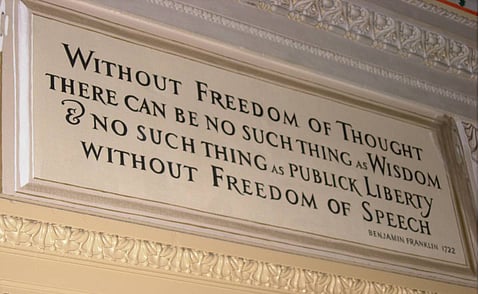

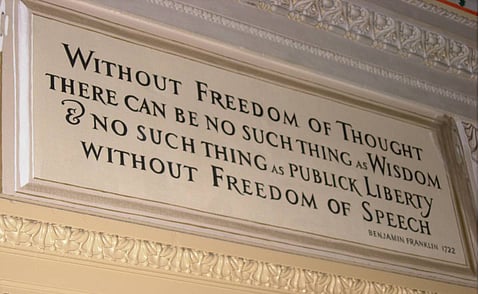

Liberty of thought is one of the shining crown jewels of our Constitution's Preamble. While the great stalwarts were busy framing the Preamble in 1948, George Orwell was preoccupied with writing his prognosticative novel 1984. The Thought Police is a terrifying entity in the novel.

It is secret police who use surveillance technology to monitor the thoughts of citizens. The Thought Police also use psychological warfare and false-flag operations to entrap free thinkers or nonconformists.

In the late 1940s, Orwell's Thought Police was a fiction and 'liberty of thought', a logorrhea. But in our days, 'brain reading' and 'Thought Police' are imminent realities, and liberty of thought, a sitting duck.

The thought process is the mental activities that constitute our thinking, which involve how we process information, from perceiving stimuli from our environment to making decisions based on that information.

As thought is an intangible internal process, it is hitherto conceived to be beyond the reach of alien external control or detection. But that era is over.

"With the help of AI, scientists from the University of Texas at Austin have developed a technique that can translate people's brain activity — like the unspoken thoughts swirling through our minds — into actual speech," according to a study published in Nature.

"Now we've got a non-invasive brain-computer interface (BCI) that can decode continuous language from the brain, so somebody else can read the general gist of what we're thinking even if we haven't uttered a single word," wrote Sigal Samuel in Vox on May 4, 2023.

Elon Musk's Neuralink and Mark Zuckerberg's Meta are working on BCIs that could pick up thoughts directly from one's neurons and translate them into words in real time.

Future of cognitive liberty

Tracking and hacking the human brain is a neuroscientific reality; not science fiction today.

"We are at a pivotal moment in human history, in which control of our brains can be enhanced or lost. We need to define the contours of cognitive liberty now or risk being too late to do so... Our brains need special protections. If they can be hacked and tracked like all our other online activities and cell phone calls, if our brains are just as subject to data tracking and aggregation as our financial records and online shopping, then we're on the cusp of something profoundly dangerous," writes Nita A Farahany in her The Battle for Your Brain: Defending the Right to Think Freely in the Age of Neurotechnology (2023).

A new challenge for mankind in the 21st century is to establish the right to cognitive liberty — to protect our freedom of thought and rumination, mental privacy, and self-determination over our brains and mental experiences.

This is the bundle of rights that makes up a new right to cognitive liberty, which can and must be recognized as part of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and enforced through the global regime of international human rights law.

Article 18 of the UDHR affirms that "Everyone has the right to freedom of thought." Even though mental privacy is not explicitly mentioned in this Article, it is widely recognized that the timely interpretation of human rights law and novel challenges to human dignity would elevate mental privacy and cognitive liberty up to the pedestal of a distinctive human right.

The United Nations Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Thought and Religion, Dr Ahmed Shaheed, submitted The Freedom of Thought report in 2021. It has been the first attempt to comprehensively articulate the content and scope of the freedom of thought in the United Nations system.

Drawing on international jurisprudence, scholarship, and the perspectives of diverse stakeholders, the Special Rapporteur proposed four attributes of this right: freedom not to disclose one's thoughts; freedom from punishment for one's thoughts; freedom from impermissible alteration of one's thoughts; and an enabling environment for freedom of thought.

Totalitarian intrusion

"Freedom to think is absolute of its own nature; the most tyrannical government is powerless to control the inward workings of the mind", the United States Supreme Court observed in Jones v. City of Opelika (1942).

But this dictum holds little water in our dystopic Digital Age when even our neurons are not insulated from state surveillance and manipulation. Now we are left to confront a grave threat to our mental privacy and cognitive liberty with outdated legal provisions and precedents.

"Totalitarian systems assume their own infallibility and seek total control over the totality of people’s lives. Before the invention of the telegraph, radio, and other modern information technology, large-scale totalitarian regimes were impossible.

"Roman emperors, Abbasid caliphs, and Mongol khans were often ruthless autocrats who believed they were infallible, but they did not have the apparatus necessary to impose totalitarian control over large societies," writes Yuval Noah Harari in his Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks from the Stone Age to AI (2024).

Alarmingly, advances in technologies like neurotechnology and AI often sharpen the totalitarian claws.

In June 1989, a few months before the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Iron Curtain, Ronald Reagan declared that "the Goliath of totalitarian control will rapidly be brought down by the David of the microchip".

But the same microchip, an epitome of technological progress, is intruding into our neurons like a mischievous Trojan horse.

To hold back this intrusion, state and civil society must develop legal shields to protect individuals' neural data. It is inescapable to allay the fears of Venkiteswarlu and his ilk.

(Faisal CK is Deputy Law Secretary to the Government of Kerala. Views are personal. Email: faisal.chelengara10@gmail.com)