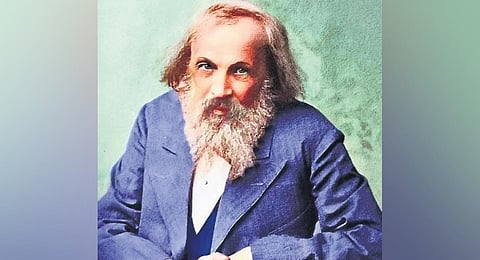

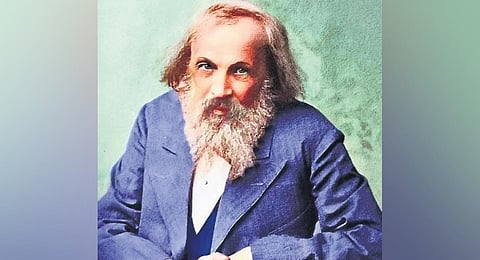

As students, any chemistry with chemistry was jeopardised while memorising the periodic table. Staring at the table of elements arranged in order, there was no excitement but agony. Dmitri Mendeleev would trim his beard and hair once a year. No exception even for the Czar. Assiduously forming the periodic table, he was also an unwavering lover. Mendeleev was 47 when he fell for an art student, Anna Popov, 17. He followed her to Rome, and in 1881 proposed marriage.

The Russian Orthodox Church had stipulated a seven-year interval. Next year, he found a willing priest, who performed the ceremony. Born in 1834 in Siberia, Mendeleev was the youngest of over a dozen siblings. His ideas began taking shape in 1869 as views of various chemists clashed, but Mendeleev remained unflinching. In March that year, the first rough sketch of the table was presented to the Russian Chemical Society; response was tepid.

His revised diagram in 1871 is more familiar in modern scientific circles. However, he could not foresee that atomic numbers instead of weights would later become the table’s ordering principle. He left gaps for undiscovered elements to complete the pattern. First gallium, then scandium and germanium – all matched his predictions. No longer Mendeleev’s table could be ignored, despite its anomalies. His chart was vertical, organising 63 known elements by their atomic weights. Elements with similar properties were placed in horizontal rows. In 1900, the future Nobel laureate in chemistry William Ramsay called it “the greatest generalisation which has as yet been made in chemistry.”

An outspoken liberal, he resigned as a professor in 1890 over the government’s quelling the students’ protest. Instead of excoriating him, Mendeelev was appointed head of the Russian government’s weights and measures in 1893. In 1906, he was nominated for the Nobel Prize and gained the support of the chemistry panel. But his severe criticism of Swedish physical chemist Svante Arrhenius’s dissociation theory ensured he would not hold the coveted award. The periodic table was too old as a discovery, he was told. Arrhenius became the first Swedish Nobel Laureate in 1903. After his death in 1907, a myth about Mendeleev was that he had set vodka’s 40% standard strength. He was nine years old when the Russian government introduced it.