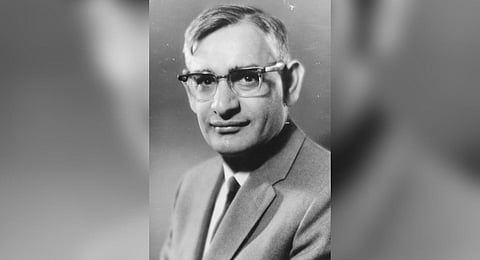

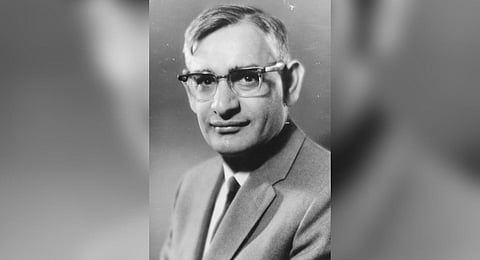

Like any other middle-class family, his parents pumped all resources into his education. Upon receiving the Nobel Prize in Physiology in 1968, Har Gobind Khorana said, “Although poor, my father was dedicated to educating his children and we were practically the only literate family in the village inhabited by about 100 people.”

Born in 1922 in Raipur, a small village, he was the youngest of his family.

During his postdoctoral work at Switzerland’s Federal Institute of Technology, he met his wife, the late Esther Elizabeth Sibler, who he said, “brought a consistent sense of purpose in my life.” For eight years, he worked on proteins and nucleic acids in Vancouver, and in 1960 became the co-director of the Institute of Enzyme Research at the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Although the Nobel came for elucidating genetic code, 4 years later he described the total chemical synthesis of a functional tRNA gene published in an entire issue of the Journal of Molecular Biology in December 1972 spanning 313 pages. Uttam L RajBhandary, who joined Khorana’s lab as a postdoc in 1962, wrote in Nature, “He often said: ‘If you have to get far, you have to travel alone’.” So, he was among the last at the university to know he had won the Nobel.

“He had gone to a rented cottage by a lake outside Madison...His wife Esther had to drive over to give him the news,” he recalled.

Thomas Sakmar who met Khorana in 1984, wrote that later he came to know about the childhood of the pioneer of molecular biology. He woke up early and looked for a house billowing smoke, and asked for some embers to light the cooking fire at home. He would also transcribe letters for the townsfolk. But destiny had everything chalked out. In 1945, he moved to the University of Liverpool to study insecticides and fungicides.

There was no space and so he was asked to pursue organic chemistry. Khorana later turned towards cellular components, including biomembranes and in the visual system rhodopsin, which is the primary photoreceptor molecule of vision. Three days before Khorana passed away on November 9, 2011, he had discussed glucose and the brain with RajBhandary.