NEW DELHI: At the midweek of the global plastics stocktake, the fifth and final session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC-5) in South Korea’s Busan is yet to decide what all should be included in the mandate—from a cut in production to regulating toxic chemicals used in making polymers. The final text of the agreement is due on December 1.

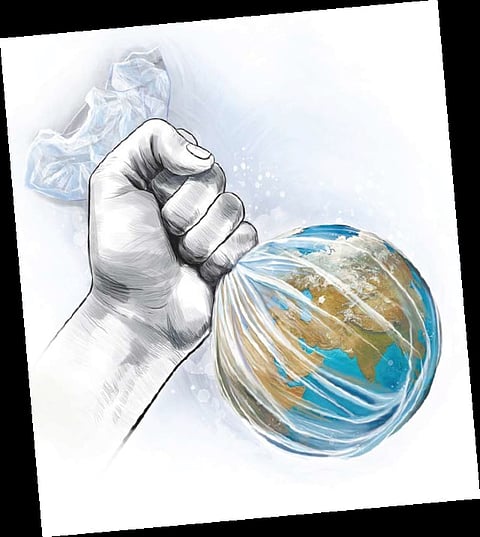

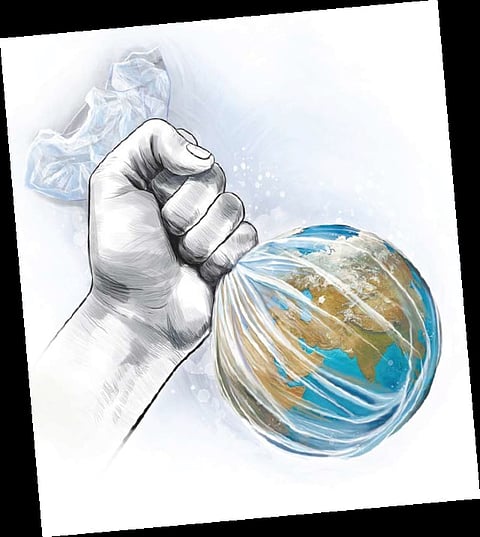

However, environmental experts are dismayed at the way the negotiations have been progressing. For, the oversized presence of fossil fuel lobbyists threatens to turn the critical environmental agreement into a charade, undermining serious efforts to curb plastic production and pollution. They worry the final text may not craft a strong way forward to make the planet plastic-free.

Financial mechanism

India proposed a dedicated multilateral fund to compensate developing countries for their transition towards plastic-free living. The fund would help developing nations meet the additional costs of transition and invest in alternative sustainable materials, India argued.

Around 100 other countries, including the African and Latin and Caribbean Group, made similar proposals like establishing a new, independent, adequate, and accessible financial mechanism to support developing countries meet their obligations under the proposed treaty.

Workable consensus and equity-based model

The developed countries group, which has 37 members, too, proposed a financial mechanism with a rider. It said no separate fund would be set up, but finance can be availed from existing multilateral mechanisms.

However, India, like other developing countries, proposed a new treaty with fresh funds and no overlap with the mandates of other multilateral agreements. In this regard, it issued a statement on the fourth day of negotiations, stating that the mandates of other multilateral environmental agreements, such as the Basel, Rotterdam, and Stockholm Conventions and international bodies like the World Trade Organization, are different from those of the treaty. These previous conventions are still debatable, and many countries still need to adopt them, India pointed out.

India also sought the transfer of clean technology to developing countries to enable compliance with control measures agreed in the instrument. India has long opposed any legally binding international treaty on plastic pollution, preferring a voluntary and consensus-based approach to combating the menace.

On Day 1 of the negotiations, India, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Egypt and Uganda called for consensus as a decision-making process for the treaty. Consensus gives individual countries the power to veto select treaty measures. However, a civil society group, Break Free From Plastic, criticised India’s position and dubbed it a ‘spoiler’.

Reduce production

Kenya proposed the phasing out of dangerous chemicals used in polymers and other problematic products and demanded transparency in the plastics manufacturing phase out with a clear deadline. Island nations proposed a 40% reduction of production levels by 2040 based on 2025 levels. India has always been against capping the manufacture of polymers—raw materials for the production of plastics by the petrochemical industry. The country has one of the world’s largest petrochemical industries.

“As discussions are underway, India may dilute its stand on polymer supply and agree to cut production,” says Siddharth Ghanshyam Singh of the Centre for Science and Environment, who is at Busan. India generated around 3.5 million tonnes (MT) of plastic waste in 2020-21, but it can recycle less than half of it. However, the per capita consumption of plastic in India is just 15 kg as compared to the United States’ 139 kg and China’s 46 kg. Despite lower per capita consumption, India banned single use plastic from July 1, 2022.

Global South colonised by plastic waste

The negotiations focus on the Global South, where more than two-thirds of the annual 57 million tons of plastic pollution comes from. India, Nigeria, Indonesia and Sub-Saharan Africa are emerging as the largest sources of pollution. However, most Global South countries import raw materials like polymers from the Global North, which is synonymous with high-income nations.

Experts term the practice of exporting waste from high-income countries to lower-income nations as waste colonialism. “If the Global North is serious about ending plastic pollution, they must stop the millions of tons of plastic waste export to the Global South,” says Pui Yi Wong with the Basel Action Network (Malaysia). “This must include plastic scraps, ‘hidden’ plastic waste in electronics, synthetic textiles, waste fuels, and other products, as well as illegally trafficked plastic waste. This injustice of waste colonialism must end.”

Here is where industry lobbyists get into play. They infiltrate the negotiations and keep derailing the efforts to eliminate plastics.

Industry lobbyists

An analysis by the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) suggests the outcome of INC-5 could be derailed. Over 200 fossil fuel and chemical industry lobbyists have registered to participate, and are working to infiltrate and delay substantive progress.

Their head count is higher than the previous peak of 196 lobbyists at INC-4. This year, the chemical and fossil fuel industry lobbyists outnumbered the scientists, indigenous people groups, and many national delegates, such as Korea, the European Union combined, the Union of Small Island Countries, and Latin American and Caribbean region countries. Some lobbyists are even in national delegations, including those from China, the Dominican Republic, Egypt, Finland, Iran, Kazakhstan and Malaysia.

The top two multinational fossil fuels industries, Dow and ExxonMobil, are well represented.

Delphine Levi Alvares, Global Petrochemical Campaign Coordinator at the CIEL, claimed that these lobbyists used tactics from their climate negotiations playbook to obstruct, distract, intimidate and spread misinformation about the negotiations. They successfully weakened the biological diversity and climate talks and kept their fossil fuel industry alive and thriving.

“From the moment the gavel came down at UNEA-5.2 to now, we have watched industry lobbyists surrounding the negotiations with sadly well-known tactics of obstruction, distraction, intimidation, and misinformation,” says Alvares.

An analysis shows that the plastic economy constitutes a minuscule amount of the global economy but permanently harms the environment. The CIEL research shows that plastic production accounts for a mere 0.6% (USD 627 billion) of the worldwide economy. Reducing dependence on plastics is unlikely to impact economic growth.