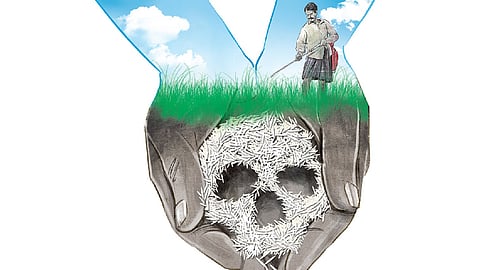

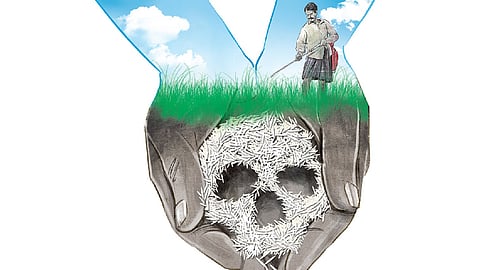

NEW DELHI: Rachel Carson’s 1962 book, Silent Spring, drew attention of the world for the first time towards the wider and harmful implications of the indiscriminate use of synthetic pesticides, especially Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), on all living organisms. It set off an environmental movement against synthetic pesticides and led to the phase out of DDT from different geographies in the world. But not in India. And Africa.

The Silent Spring period in India and Africa will continue for at least five more years. Some alternatives to DDT have been developed but experts believe they are yet to be tried and tested fully to completely replace the toxic chemical. India is the sole producer of DDT globally since 2008 (China did until 2007). It missed the deadline to phase out the deadly chemical by 2024-end under the Stockholm Convention. The Convention had outlawed the production and use of DDT and other toxic chemicals and limited it to mosquito control.

DDT, a major source of persistent organic pollutants (POPs), was developed in the 1940s to control vector borne diseases like malaria and typhus and other insect borne diseases. It was used by both the military and the civilian administration to control insects in crops and livestock production, institutions, homes and gardens.

In 1960, new evidence started coming up on POPs impacting the environment and human health and many insects developing resistance to it. These chemicals remain intact in the environment for long periods, accumulate the fatty tissue of living organisms and are toxic to human beings and wildlife.

India banned its agricultural uses by 1972. However, DDT’s illegal use continued in many parts of the country till the 1990s. Later, strict enforcement and regulations led to a complete ban on its spraying in agriculture. At present, the only consumer of DDT in India is the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. It uses it to control vector borne diseases by spraying DDT over walls in malaria-infected houses and buildings in rural and urban areas.

The health ministry has indicated it does not need DDT any longer as its alternatives are already in place. The ministry has a stock of 578 metric tonnes (MT) of DDT for its future use along with alternatives. But it has not given it in writing to the Department of Chemicals, Petrochemical and Fertilizers (DCP). DCP is the nodal committee that oversees the production and supply of DDT.

Senior government officials say it’s the demand from Africa that persuaded the country to continue DDT production. India exports the chemical to Botswana, South Africa, Zambia, Mozambique, Namibia and Zimbabwe. The Ministry of Environment, Forest & Climate Change, which is the nodal organisation under the Convention, received the opinion and consent from the Department of Chemicals and Petrochemicals for continuing DDT production to meet its export obligations. Hindustan Insecticide Ltd (HIL) has an export commitment of 36 metric tonnes of DDT to five African countries by March-end. The ministry is expected to inform the convention secretariat before the next meeting of the convention scheduled in September on the decision to continue DDT production for five more years.

“The environment ministry hasn’t given any new order to Hindustan Insecticide Ltd, the sole manufacturer of DDT. But the DCP is committed to meet African demands,” said Ved Prakash Mishra, Director, Hazardous Substances Management, at the environment ministry.

Alternatives

In 2014, India got the first extension for 10 years to phase out DDT. The country, too, had decided to phase out DDT by 2024. To do so, India has been working on some environment-friendly alternatives and may start their production by the 2025-end. “The idea of alternatives to DDT must be affordable and effective,” says Dr Ashwani Kumar, former director at the ICMR-Vector Control Research Centre.

A $50 million project of the India Council for Medical Research jointly with the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) has developed the world’s first neem-based biopesticide and Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis)-based biopesticide. These biopesticides have been found to be effective on mosquitoes eggs, larvae and pupa but are safe for other aquatic and human beings, unlike DDT which is effective on adult mosquitoes but harmful for humans and animals.

“But the tragedy is that our indigenous product has not been adopted by the National Malaria Programme. Our field research shows that it has been effective on malaria, dengue, etc. But its commercial production is yet to start,” says a scientist on the condition of anonymity. There is another product, the long lasting insecticidal net (LLIN), whose threads are impregnated with parathyroid chemicals. Mosquitoes die if they bite the net’s thread. “If mosquitoes escape biopesticides, then LLINs are the final barrier to prevent mosquito bites,” says Yash Pal Ramdev, UNIDO technical adviser in India.

However, experts doubt the efficacy of these alternatives. For instance, the supply of LLIN is poor. “India’s decision to not to completely phase out DDT is also due to concerns that if these alternatives are not effective, it will be forced to fall back on DDT,” said a senior officer at Union environment ministry.