Fossilisation is the process by which organic materials like plants, animals, and other life forms, are preserved in the Earth’s crust over geological time. Fossils provide snapshots of ancient life and environment when they existed in living form, offering invaluable insights into the history and evolution of nature. However, fossilisation in its natural form, is a rare occurrence. Most organisms decay before they can become fossilised, and of those that do get naturally fossilised, only a small proportion are preserved in a way that allows scientists to study them even after millions of years. The fossilisation process involves several stages, which begins from the death of an organism to the eventual discovery of the fossil by paleontologists.

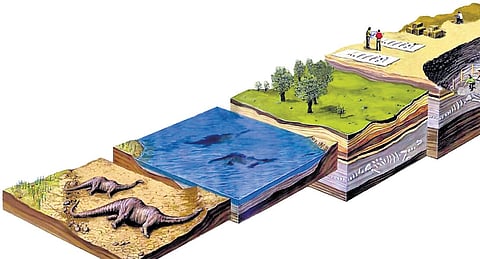

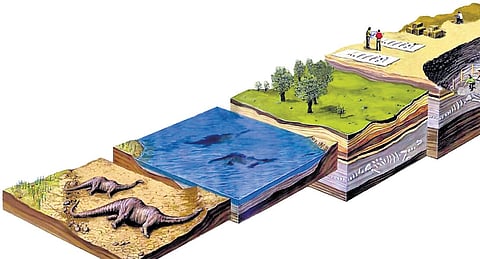

The process of any organism becoming a fossil begins the moment it dies. Whether an animal, plant, or microorganism, the initial stage is the same for all. However, for fossilisation to set in, the organism must be buried quickly after death. If it is left exposed on the surface, scavengers, bacteria, and environmental factors like weathering and decay, will break it down, making fossilisation unlikely.

The ideal conditions to preserve the body is any place with deep water, tar pits, or areas with rapid sediment deposition, where the remains may be preserved before the decomposition process can fully set in. Almost immediate burial is crucial for the process, so that it isolates the remains from environmental factors that would otherwise decompose the organism. This burial process is essential for the preservation of the organism, as the sediments protect the remains from physical and chemical breakdown. The burial also begins the process of compressing the remains, which will eventually aid in fossilisation.

Once an organism dies, it often ends up in a place where it is covered in sediments such as sand, mud, or volcanic ash. The type of sediment in which an organism is buried can significantly affect the type of fossil it results in. Aquatic organisms usually end up being buried in fine mud and silt, which are more likely to preserve delicate structures like shells or bones, while organisms buried under volcanic ash, can result in very detailed fossils. However, tar, or asphalt, can trap and preserve organisms.

The sticky nature of tar prevents scavengers from removing the remains, and the environment allows for exceptional preservation. Over time, layers of sediment accumulate over the buried remains, increasing pressure on them, which causes compaction, squeezing out remaining water in the tissues.

Most commonly, fossils of harder parts of an organism, like bones, teeth, shells, and wood end up getting preserved, because these materials are more durable than soft tissues, like muscles, skin, and organs, which decay much more rapidly. In rare cases, under exceptional conditions like extreme freezing, mummification, or entrapment in amber, soft tissues can also be preserved.

During burial, the minerals in the surrounding sediment begin to replace the organic materials in the hard parts of the organism. This process, known as permineralisation, occurs when mineral-rich water seeps into the pores and cavities of the bones, teeth, or shells. Over time, the minerals crystallise within these spaces, preserving the original structure.

This gradual, mineralisation converts the remains into a rock-like substance, like calcium carbonate or silica can replace the original material, turning the bones or shells into fossilised forms. Fossils may remain buried for millions of years, slowly becoming part of the geological record.