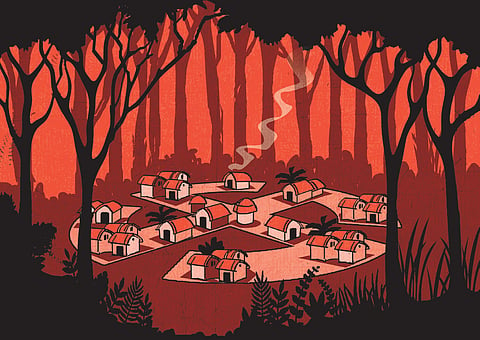

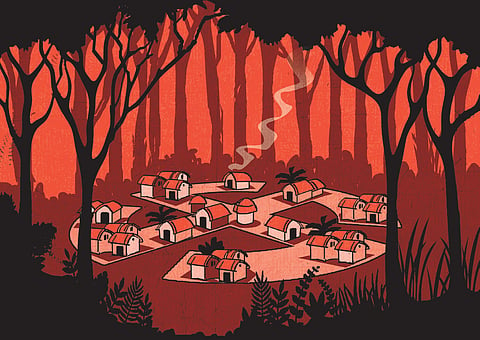

In the lush, verdant landscapes of Kerala, a battle for survival rages on. The once-thriving agricultural communities now live in fear, their livelihoods hanging in the balance.

Wayanad, Idukki and Palakkad districts have become the epicentres of this conflict, with elephants, tigers, and wild boars wreaking havoc on crops and lives. In the last 17 days, three lives have been lost to elephants and one to a tiger in these hill districts.

The authorities have tranquillised one tiger while an elephant and a tiger have been killed in the botched-up tranquilising effort by the forest department. Elephant herds continue to invade farmlands, and even towns, and tigers roam free. Wild boar, peacocks and monkey menace add to the woe of the farmers.

The tiger attacks in Wayanad have claimed seven lives in the last eight years. The lack of provisions for compensating for the loss of lives and crop damages has forced many farmers to abandon their lands, leaving behind a trail of devastation.

In what could be best described as a knee-jerk reaction, the state of Kerala has proposed amendments to Section 11 of the Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972, which deals with the hunting of wild animals. The clause (1) (A) of the section states that the Chief Wildlife Warden of a state may permit the killing or hunting of a wild animal mentioned in Schedule I if it has become dangerous to human life or diseased beyond recovery.

The state wants to transfer this power to the Chief Conservators of Forests, enabling speedy decisions at the local levels and making the procedures for managing wild animals that pose a threat to human lives easier. Since it is election season, state and central governments and the political parties of all hues are busy pointing fingers at each other while arranging competitive photo ops with the families of the hapless victims.

While the state government says the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980, is to blame, the Union Minister for Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Bhupendra Yadav, says that the state has the power to kill the wild animals that are a threat to society, but they were not utilising it.

The farmers’ plight and that of the animals is indeed a complex issue. On one hand, the farmers are struggling to protect their crops and livelihoods from the wild animals, while on the other hand, the animals are fighting a desperate battle for survival. The state has been caught in a web of confusion and indecision, unable to balance the needs of its people and the preservation of wildlife.

Over the years, the human-animal conflict has intensified due to a multitude of factors.

The state forest department’s relentless pursuit of economic gain has led to the felling of vast tracts of virgin forests, replaced by commercial crops like teak and eucalyptus. This ill-conceived policy has severely disrupted the delicate balance of the ecosystem, leading to a scarcity of water and food within the jungle.

The consequences are dire. Desperate for sustenance, animals are forced to venture out of their natural habitats. Farmlands have become their new hunting grounds, as they raid crops and compete with humans for dwindling resources.

The state government’s policies had often prioritised short-term economic gains over environmental conservation. The conversion of forest land for cash crops, such as rubber and coffee, has led to the fragmentation and degradation of natural habitats. Invasive species, such as the lantana weed and the acacia, have further exacerbated the problem. These non-native plants had rapidly spread throughout the forests, out-competing native vegetation and reducing the availability of food for wild animals.

The regularisation of encroachment of the forest through ‘Pattayam Melas’ has also played a significant role in deforestation. These land grants have allowed people to settle within the forests, leading to further fragmentation and habitat loss. This fetched easy votes in the short term, but now there is a terrible price to pay. The irony is palpable. The very department tasked with protecting the state’s wildlife has inadvertently created the conditions that were driving animals into conflict with humans.

There is no easy way out of this quandary. But one can start by depopulating the villages bordering the forest lands by paying substantial compensation for the land thus taken over. The commercial exploitation of the forests by planting teak trees should be stopped and the forests should be returned to their pristine states. These are not foolproof measures, but this would be a good beginning and is better than shooting every animal that strays or ignoring the plight of poor farmers.

Anand Neelakantan

Author of Asura, Ajaya series, Vanara and Bahubali trilogy

mail@asura.co.in