The State Bank of India has asked for nearly four months to furnish the data on who deposited money into 22,217 electoral bonds and who took out the money from them.

This may sound like a job that should take only a few minutes for a fully computerized bank like SBI, and many have wondered why the bank is asking for four months to furnish this data as directed by the Supreme Court.

Before trying to understand SBI's argument, it is important to understand how electoral bonds work:

To donate money to a political party, a person or company has to first to go to any of the 29 designated SBI branches.

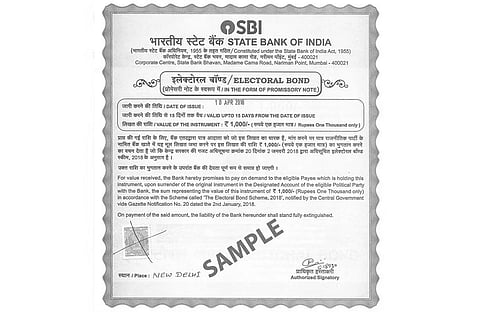

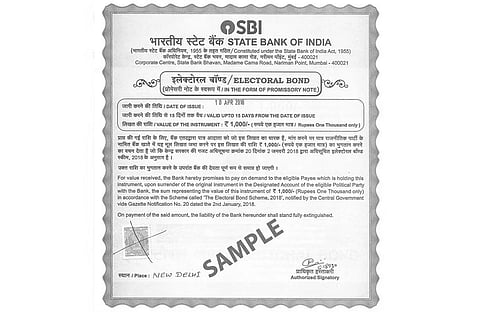

There, the person deposits the money at the branch and collects the 'bonds' -- somewhat like how one would create a demand draft. The difference between a demand draft and an electoral bond is that the demand draft will have the name of both the payer and the payee, but an electoral bond will have neither of these. In other words, if you created an electoral bond and you lost it on your way home, and there is no way for anyone to track it back to you or to figure out who you wanted to gift this to. In terms of anonymity, these 'bearer bonds' are next only to cash.

As a first step, therefore, you would walk into any of the 29 SBI branches and say that you want to create an electoral bond of Rs 50 crore. You would then pay Rs 50 crore to the bank and the bank would issue you 50 certificates, each worth Rs 1 crore.

After that, SBI will enter the details of this transaction on a sheet of paper, but not into its computers. It would then put this paper inside a sealed cover, and send it to SBI's central office in Mumbai. SBI did not enter the details into its computer systems to respect the privacy of the donor and the party which gets the money.

After getting hold of the 50 bonds, the person walks out of the bank and goes to his favorite political party.

Here, the person hands over the bonds and walks out.

Someone from party then goes to SBI and deposits the electoral bond for redemption -- much like you would deposit a cheque -- along with the party's account details.

SBI then credits the amount to the party's account.

Now, let's try to understand why SBI feels it needs 4 months to give the data.

The first point it has raised is that it has issued nearly 22,217 bonds during the four years under question.

This means that the total number of transactions could be in the thousands. For example, even if one assumes that each person purchased 10 bonds on average, this would imply that there were close to 2,222 transactions in all.

Since each transaction would be recorded in a different envelop, there would 2,222 envelopes in all.

These envelopes are all lying in SBI's central branch in Mumbai.

Now, these envelops only cover the deposit aspect of the deal.

Each time a party functionary came and redeemed a bunch of electoral bonds, that transaction too would be recorded on paper and a sealed cover would be created.

This means that there would another 1,000 or 2,000 sealed covers lying in a different bag -- corresponding to the redemptions.

SBI says that both of these sets of sealed covers are kept as they are, and that it did not try to track who donated to which party by opening the envelopes. In other words, these two sets of envelopes represent two 'silos' of information that have not been matched with each other.

The Supreme Court, however, has asked SBI to do exactly that -- come up with details of who donated to which party and how much.

To find out whose money went to which party, SBI will have to now open the first set of envelopes (donation details) -- create a list of donors, and against each donor, note down the details of the certificate issued to that person.

It would then open the second bag of envelopes, create a list of political parties, and against each party, give a list of certificates that they had deposited.

Once the two lists are complete, it would then match these two lists to come up with a new list of who gave how much money to which party.

However, the above method assumes one key fact -- that each transaction slip contains the unique ID of the bond issued or redeemed.

In case such a unique ID did not exist, or if SBI did not record the unique ID in its transaction slips, then it will have to first establish which bond was involved in which transaction by matching the creation date of each bond with the transaction date given in the paper slips.

From SBI's statement to the court, it would seem that there was no such ID in the transaction details, and that it would have to link each certificate to each transaction purely by looking at the date of creation and branch name. "To make available donor information, the date of issue of each bond will have to be checked and matched against the date of purchase by a particular donor," SBI said.

The absence of a unique identifier would make it difficult to track the movement of the certificates that were created on a day when more than one person or company walked into the same bank branch to create electoral bonds.