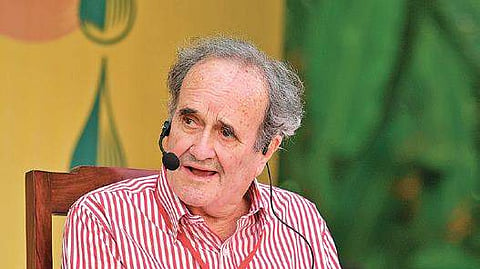

The voice of the Englishman from Tollygunge has fallen silent.

Mark Tully passed away at a Delhi hospital at 90 on Sunday. He leaves behind a formidable legacy as one of BBC’s most trusted chroniclers: For decades, listeners across South Asia grew into the habit of tuning in to Tully, awaiting his voice to confirm events and trusting his account as the measure of truth.

Born in Kolkata to British parents, Tully spent his early years in India before being sent to England for his education. He returned in 1964 as the BBC’s India Correspondent and eventually became Bureau Chief in New Delhi, a post he held for nearly three decades and reported on the birth of Bangladesh, military rule in Pakistan, the Tamil Tigers’ insurgency in Sri Lanka, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

Tully’s reporting was distinguished by both authority and empathy. He covered some of India’s most turbulent moments: the Emergency of 1975–1977, Operation Blue Star, the assassination of Indira Gandhi and the anti-Sikh violence that followed, and the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992. Generations of listeners, who affectionately called him “Tully Sahib,” relied on his thoughtful analysis and precise narration to understand events often mired in chaos. His integrity sometimes placed him in danger: Andrew Whitehead, a former BBC colleague, recalled Tully’s peril in Ayodhya in 1992, when a mob threatened him, chanting “Death to Mark Tully,” and he was locked in a room for hours before being rescued by a local official and a Hindu priest.

His work also reflected his concern for the state of journalism. In an interview with journalist Malvika Banerjee, he said, “The problem is that the institutions which should control politicians and prevent them from running away with everything are not sufficiently strong. And the voice of the people is not sufficiently heard, because politicians get away with so much.” A prolific writer, among his important works are No Full Stops in India (1988), which collected decades of reflections on the nation he chronicled so faithfully, India in Slow Motion (1998), and Nonstop India (2003), each offering insightful, empathetic portraits of India’s social, political, and cultural life.

Tully’s career also highlighted the BBC’s evolving relationship with India. According to the BBC History series, the corporation’s legacy as a former imperial broadcaster and its enduring credibility with Indian audiences after independence created a complex relationship with successive Indian governments. In 1970, the airing of two Louis Malle documentaries sparked strong objections from both the Indian government and the diaspora in Britain, leading to the BBC’s expulsion from India until 1972. Around this time Tully was flowering into the catalyst he would eventually become for London and New Delhi, maintaining respect for the people and cultures he reported on.

Beyond his professional life, Tully’s personality shone through in personal touches shared by his family. On his 90th birthday, his son Sam Tully wrote, “‘Dill hai Hindustani, magar thoda Angrezi bhi!’ The heart is Indian but a bit English too!...He was just as happy with bacon and eggs as biryani…” These glimpses reveal a man whose life bridged worlds—not only professionally, but in his tastes, habits, and affection for both countries he called home.

Despite occasional criticism for being too indulgent of India’s inequalities, Tully remained committed to fairness and to conveying the nation’s diversity and resilience. He was knighted in 2002 and received the Padma Shri and Padma Bhushan—a rare dual recognition of a life spent bridging two nations. Though he retained British citizenship, he later became an Overseas Citizen of India, describing himself as belonging to both countries.

In his passing away, India has lost one of its most perceptive and affectionate witnesses. But the clarity, compassion, and insight that characterised his work will continue to resonate.

He is survived by the countless listeners, readers, and colleagues whose lives he touched, and by the example of a journalist who understood that to tell a nation’s story fully, one must first listen to it.