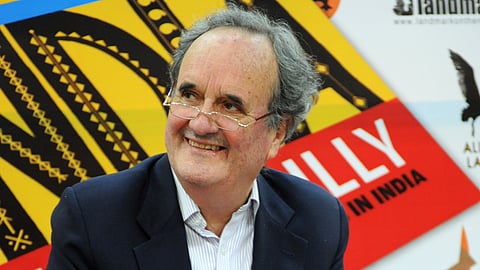

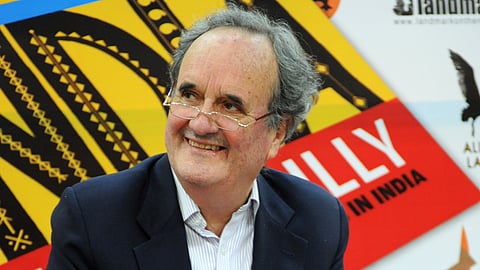

There are journalists who report events, and there are the rarer ones who shape generations. Sir Mark Tully decisively belonged to the second kind.

When the news came, on a grey January morning, that the world-renowned journalist had died in Delhi at the age of ninety, it felt less like the passing of a man. It was more the extinguishing of a certain tone of voice—grave, unhurried and gently probing that rose from the BBC World Service and found its way into countless Indian homes, including mine.

For a generation that learned to make sense of politics through a transistor radio, Mark Tully was not merely a correspondent. He was a companion in confusion and a guide through the labyrinth of a country trying to understand itself.

Learning the country through his voice

I first encountered him not through print but through sound.

The ritual was simple: evening light fading, radio tuned carefully, the familiar signature tune, and then that voice—calm, faintly foreign and unmistakably intimate—narrating India back to itself. In those years, before the tyranny of breaking news and the performative certainties of television debates, news still arrived as a narrative.

Mark Tully's dispatches did not assault you; they invited you in. He did not begin with conclusions. He began with people.

In a media culture now obsessed with verdicts, he practised description. He allowed events to unfold slowly, trusting the listener to arrive at understanding without being pushed.

Journalism, for him, was not the art of persuasion, but the discipline of attention.

More than thirty eventful years

Born in 1935 in Calcutta, educated partly in India and then in England, Tully carried with him the complicated inheritance of a colonial childhood and the restless curiosity of a postcolonial witness. He returned to India as a young BBC correspondent in the 1960s and stayed, not as a temporary visitor but as a resident chronicler of a nation in motion.

Over three decades in Delhi, including more than twenty years as the BBC's bureau chief, he did what few foreign journalists have done with such consistency: he refused to remain foreign.

This refusal was not ideological; it was ethical.

He learned Hindi, not merely to manage interviews but to truly understand. He travelled beyond the metropolitan enclaves, into small towns and villages, into police stations and courtrooms, into the waiting rooms of grief and expectation. He waited. He listened.

Long before "ground reporting" became a professional slogan, Mark Tully practised it as a moral instinct.

The BBC years and the craft of restraint

His years at the BBC coincided with the shaping decades of modern India.

From the Bangladesh war of 1971 to the Emergency, from Bhopal to Operation Blue Star, from the assassinations of Indira and Rajiv Gandhi to the long shadows of communal violence, Tully stood at the crossroads of history and narration.

Yet what distinguished his journalism was not access but temperament.

He distrusted easy moralities. He resisted the seduction of grand theories.

Others looked for villains and heroes, but such binaries were not for him.

He belonged to a generation of correspondents who believed that the first duty of journalism was not to be interesting, but to be right.

In that newsroom culture, speed was never an excuse for carelessness, and proximity to power was never a licence for complicity.

With Satish Jacob: A school of journalism

In this, he was not alone.

His long and productive association with Satish Jacob at the BBC remains one of the most consequential partnerships in Indian broadcast journalism. Together, Tully and Jacob created not merely reports, but a newsroom that combined institutional rigour with local intelligence.

If Tully brought the patience of the outsider determined to understand, Jacob brought the instincts of the insider determined to explain. Between them, the BBC's Delhi bureau became a school.

Young reporters passed through there and carried with them that discipline: verify before you publish, listen before you interpret, resist the pressure of proximity to power.

Many of those who later shaped Indian print and television journalism learned their first lessons in accuracy, restraint, and narrative ethics under Tully's watchful eye.

In that sense, his greatest influence may not lie in what he wrote, but in whom he trained.

He inspired generations not by instruction manuals, but by example.

Teaching a generation how to doubt

Listening to him as a young man, I learned something that no textbook taught me: that journalism is not the art of certainty but the discipline of doubt.

He rarely raised his voice. He rarely simplified. He allowed contradiction to remain visible.

There was, in his style, something of the old liberal conscience, sceptical of authority, wary of slogans, allergic to hysteria. But there was also a deeper empathy, born perhaps of his own uneasy position between cultures.

He knew what it meant to belong imperfectly.

That may be why he was drawn so persistently to the margins: to farmers caught between debt and dignity, to minorities trapped between fear and faith, to officials torn between procedure and conscience.

He was, in the best sense, a moral journalist, not because he preached, but because he cared about consequences.

What India meant to Mark Tully

To ask what India meant to Mark Tully is to ask what gave coherence to his life.

India was not merely his posting; it was his chosen home.

Long after retirement, long after honours and recognition, he chose to live in Delhi, to remain immersed in the country's daily rhythms. He wrote often about his belief that India's greatest strength lay in its stubborn pluralism, its capacity to accommodate contradiction without collapsing into uniformity.

He admired Indian democracy not because it was efficient, but because it was resilient.

He worried about its erosion, not because he was nostalgic, but because he had seen, first-hand, how fragile institutions become when language hardens and power grows impatient.

In India in Slow Motion, he offered his most precise metaphor: a country moving unevenly, hesitantly, sometimes backwards, often sideways, but always with an inner momentum that defied simple diagnosis.

That phrase captured both his understanding of India and his philosophy of journalism.

Progress, like truth, is rarely dramatic. It is cumulative.

The quiet influence

It is difficult to explain to younger readers what such journalism felt like, because the ecosystem has changed.

Today, speed is virtue, outrage is currency, and complexity is inconvenience. In Tully's time, patience was a professional ethic.

And yet, paradoxically, he was interesting precisely because he refused to chase interest.

His books, No Full Stops in India, India in Slow Motion, and The Heart of India, were extensions of his radio voice: reflective, sceptical, humane. He wrote about democracy not as an abstraction but as a daily negotiation between state and society, law and habit, promise and disappointment.

Despite honours—a knighthood from Britain, the Padma Bhushan from India—he remained fundamentally uncomfortable with authority. His instinct was always to look downwards, not upwards: towards those who bear the costs of decisions made elsewhere.

An ending, and a standard

For me, and for many like me, his greatest legacy is not a particular report or book, but a habit of attention.

He taught us to listen before we speak. To describe before we judge.

To slow down before we conclude.

In an era when journalism increasingly resembles performance, Mark Tully reminds us that it once aspired to be a form of public service.

There is, in the memory of his voice, a certain quiet that now feels extinct.

When I think back to those evenings with the radio, what strikes me is not the information I received but the attitude I absorbed: that history is made by ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances; that truth is provisional; that explanation is more valuable than accusation.

His death closes a chapter in the story of Indian journalism, the chapter in which the foreign correspondent was not a parachute visitor but a long-term witness; in which mentorship mattered as much as bylines; in which distance produced not detachment but perspective.

We will continue to write about India, and perhaps we will write faster, louder, sharper. But it is worth pausing, at this moment, to remember a man who wrote slowly, spoke softly, trained generously, and understood deeply.

Mark Tully might be gone. But the method he practised—patient, humane, attentive—remains a standard against which all of us who write about this country must continue to measure ourselves.

In the end, that may be the truest obituary.

(Ashutosh Kumar Thakur writes regularly on society, literature, and the arts, reflecting on the shared histories and cultures of South Asia.)