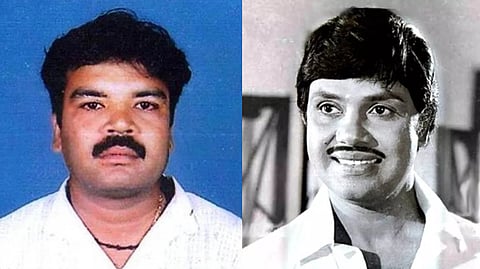

He was the original action hero, a man who dared to do what no one else would. On November 16, 1980, Malayalam superstar Jayan strapped himself to a dream—and a helicopter. While shooting the climax of Kolilakkam in Sholavaram near Chennai, he leapt from a moving motorcycle onto a hovering Bell 47. The scene was already in the can, but Jayan, ever the perfectionist, wanted a retake. What followed was horror: the helicopter spun out of control and crashed. Jayan was killed instantly. He was 41.

More than four decades later, the story repeats itself—this time in Nagapattinam, Tamil Nadu.

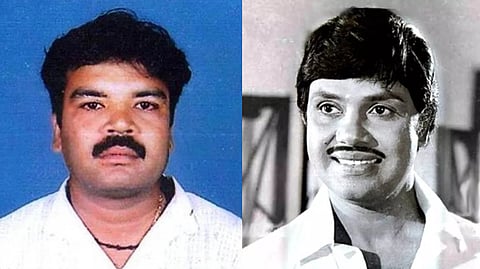

On July 13, 2025, S. Mohanraj, known in the industry as SM Raju, one of Tamil cinema’s seasoned stunt masters, died performing a high-speed car stunt for director Pa Ranjith’s upcoming film Vettuvam. The vehicle overturned during filming. He was rushed to the hospital but could not be saved.

These aren’t isolated tragedies. Last year, a car chase gone wrong during the filming of Bromance left actors Arjun Ashokan and Sangeet Prathap injured, prompting a Motor Vehicles Department case for overspeeding. In 2016, two stuntmen drowned during the shoot of Masti Gudi, a Kannada film. The two—Uday Raghav and Anil Kumar—jumped from a helicopter into a reservoir without life jackets. They drowned. The film’s lead actor, who wore a life jacket, survived.

Cinema thrives on spectacle. But behind the slow-motion punches and fiery crashes lies a stark truth: India, despite its billion-dollar film industry, still lacks a proper safety framework for its most vulnerable contributors—the stunt artists.

And each time one of them dies, the same questions echo: Who is responsible? Why is there still no law? And how many more must be sacrificed before the industry acts?

“It was an unfortunate incident. And it’s rare, too. But his safety should have been ensured,” says Sandeep Senan, producer and joint secretary of the Kerala Film Producers Association (KFPA), referring to SM Raju’s death.

The responsibility, according to industry insiders, often lies not with the producers or directors, but with the stunt masters themselves—the very people risking their lives.

“In most Malayalam films, it is the stunt master and his team who arrange the safety equipment—ropes, belts, crash mats, all of it,” says veteran stunt director Mafia Sasi. “The production team gives us the scene and the expectations, but how it’s done is entirely our call.”

Stunt masters operate as self-contained units—bringing their own crew, gadgets, and training. This practice, industry veterans say, is both an empowerment and a liability.

There’s no written guideline

“There’s no structured guideline or national protocol to follow,” says Manoj Mahadev, secretary of the Stunt Artists and Masters Association (SAMA) in Malayalam cinema.

“Every stunt is different. Still, we rehearse, we train the actors, we prepare—but we operate in an unregulated space.” Manoj adds that even though stunt artists have years of experience, complacency and overconfidence can be fatal. “Every stunt must be treated with fresh caution. That’s why safety gear is non-negotiable,” he says.

What further complicates the issue is the lack of binding agreements. “We cannot ask a stuntman to sign a paper saying he accepts the risk of injury or death. That’s not ethical. And legally, it doesn’t hold up,” says Manoj.

Following the death of SM Raju, the All India Cine Workers Association (AICWA) announced that it would press Union Labour Minister Mansukh Mandaviya for a national safety law governing the working conditions of stuntmen and cine technicians involved in high-risk shoots.

An uninsured life

Arguably the most gaping hole in the safety net is insurance—or the lack of it. For years, stunt performers were classified as “uninsurable” by most insurance firms due to the nature of their job.

“In Tamil Nadu, we are still fighting to get proper coverage,” says stunt coordinator Don Ashok. “Insurance companies see us as too risky. Even after years of negotiation, we’ve only managed to get a basic accident policy for stunt masters, covering up to Rs 1 lakh. The rest of the team still remains outside the safety net.”

In Kerala, the scene is marginally better. “In recent years, more private insurance providers have started offering policies to stunt artists,” notes Mafia Sasi. “But it’s still not institutional. There’s no mandate.” Without insurance, a serious injury can end a career—and push families into debt. “We’ve had people bedridden for months after accidents,” says Manoj. “And unless the producer steps in out of goodwill, there’s no financial cushion.”

Lessons rehearsed, not always learned

Fight scenes are meticulously choreographed. But that doesn’t always guarantee safety. Rehearsals, like dance routines, are common. “Before big fight scenes, especially those involving lead actors, we conduct several days of training,” says Sasi. “Even now, some actors travel to Chennai or Mumbai to learn the basics.”

However, this preparation is not uniform across the industry. “For small-scale stunts—maybe a fall or a slap—there’s often no training or rehearsal,” he says. “That’s where mistakes happen. Because even the simplest action can go wrong if not timed correctly.”

During the shooting of Anniyan, a rehearsal turned disastrous when a rope snapped, causing more than 20 stuntmen to fall from a height. Many suffered serious injuries and required prolonged treatment.

Stunt unions hold the fort

In the absence of government regulation, it is the stunt artists’ unions that try to enforce basic safety. “Usually, the union ensures that the team has the necessary equipment and experience,” says Senan. “In Malayalam cinema, the FEFKA stunt masters’ union is quite strong. But often, for major sequences, we also bring in teams from Tamil Nadu, which requires inter-union coordination.”

The unions also intervene in case of accidents, helping negotiate treatment expenses and insurance claims where applicable. But they, too, are limited in what they can do without systemic backing.

Time for a national safety code?

As Indian cinema pushes into more ambitious visual territory—with pan-Indian releases, international shoots, and CGI-enhanced action—the risks faced by real bodies on real sets remain under-addressed.

“We’re providing a full package—people, gear, training, execution—but we need the industry to acknowledge the risks and support us,” says Manoj. “We are not just background workers. We are frontline professionals.”

The call for a national stunt safety code is not new. But with each fresh accident—each funeral, each fractured spine—it becomes harder to ignore. “It shouldn’t take another Jayan, another Raju, to remind us that our lives are on the line every time the director yells ‘Action!’” says Sasi.

Until laws are passed, insurance is mandated, and proper guidelines are enforced, India’s action scenes will remain what they’ve always been—thrilling for the audience, terrifying for the artist. And for those who leap from bikes to helicopters, it will always be more than just a stunt. It’s a gamble with death.