The resurgence of linguistic nationalism in India poses a grave threat to the country’s pluralist ecosystem. The state-sponsored dominance of a single language over others not only undermines cultural federalism but also disrupts the socio-religious and regional equilibrium envisioned by the Constitution.

The language debate in India has once again intensified, with Tamil Nadu Chief Minister MK Stalin recently rejecting the implementation of the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 in his state.

He accused the Union government of attempting to impose Hindi under the guise of the three-language policy. "The Centre is doing politics by promoting Hindi in a country where people speak different languages. I will not allow Hindi imposition in Tamil Nadu," he declared.

India is currently witnessing two distinct forms of linguistic hegemony. First, a Sanskritized version of Hindi is being aggressively promoted at the expense of Hindustani—a more inclusive language that historically blended elements of Hindi, Urdu, and regional languages. Second, linguistic majoritarianism is being reinforced at the state level, where non-dominant linguistic communities are increasingly marginalized.

Adding to this linguistic fanaticism is a growing hostility toward English, which further exacerbates social and economic disparities.

Union Home Minister Amit Shah, as Chairperson of the Parliamentary Committee on Official Language, recently underscored the government’s intent to expand Hindi’s footprint.

In September 2024, he stated that by 2047, all government systems would operate in Indian languages. He further argued that Hindi, a "1,000- year-old" language, needed revitalization, claiming it was a mission left unfulfilled by the freedom fighters.

However, these assertions lack historical accuracy, as Hindi only evolved as an independent language in the late 18th century, and linguistic nationalism was never a major credo of India’s freedom struggle.

In another instance of state-backed linguistic chauvinism, the Maharashtra government issued an order on February 3, 2025, making Marathi mandatory for all government employees.

The directive also allows citizens to file complaints against officials who do not use Marathi. This is problematic, considering that only 72.37% of Maharashtra’s population speaks Marathi, with the remaining population comprising speakers of Urdu, Hindi, Gujarati, Telugu, Kannada, Bhili, and Khandeshi. Such policies are inherently discriminatory against intra-state linguistic minorities.

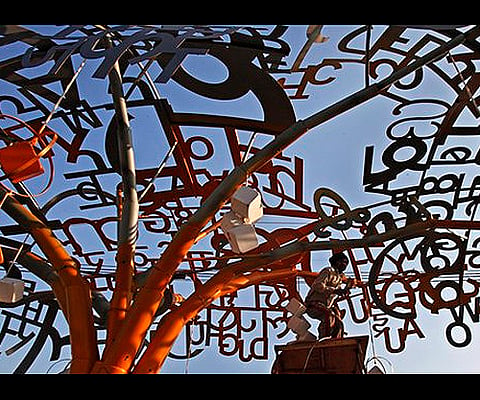

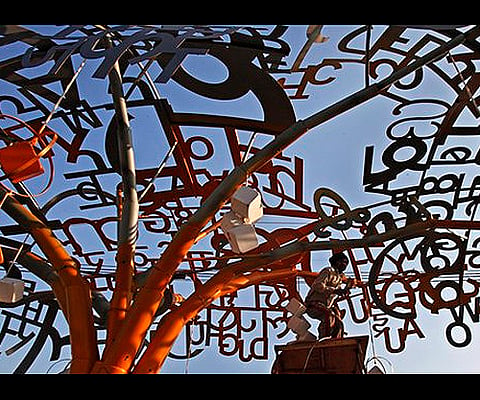

The government’s tacit endorsement of linguistic chauvinism is dangerous. If unchecked, it will erode India’s cultural pluralism and push the nation toward social and political disarray—a perfect babel of linguistic discord.

Reclaiming ‘Rainbow Hindustani’

The debate over an official language was one of the most contentious issues in the Constituent Assembly. The Munshi-Ayyangar formula eventually led to the adoption of Hindi in the Devanagari script as an official language, alongside English, which was to continue for 15 years. However, non-Hindi-speaking states, particularly Tamil Nadu, strongly opposed Hindi's elevation. The Official Language Act of 1963 ensured that English would continue as an associate official language, and the 1967 amendment granted state governments the power to retain English indefinitely if they so desired.

During these debates, a faction of militant Hindi proponents, led by Purushottam Das Tandon and Seth Govind Das, fiercely opposed Hindustani—a more inclusive blend of Hindi and Urdu. They insisted that only a Sanskritized Hindi in the Devanagari script could be the national language. Their insistence on linguistic homogeneity was not only shortsighted but also deeply divisive. As sociologist TK Oommen noted in Nation, Civil Society, and Social Movements: Essays in Political Sociology (2004), there exists an intrinsic link between language and religion in India—Tamil is associated with Dravidian Hinduism, Sanskrit with Aryan Hinduism, Pali with Buddhism, Urdu with Islam, Punjabi with Sikhism, and English with Christianity.

Thus, imposing one language at the expense of others disrupts India’s delicate socio-religious balance and undermines cultural federalism.

Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru championed an inclusive Hindustani as India’s national language. The Nehru Report of 1928 advocated for Hindustani — a language enriched by Hindi, Urdu, Punjabi, and even English vocabulary. As per the 1951 Census, Hindustani was spoken by 45% of the Indian population. However, Hindi hardliners resisted it, determined to impose Hindi despite strong opposition.

Zahirul Hasnain Lari, a member of the Constituent Assembly from Uttar Pradesh, resigned in protest when Hindustani and Persian script were sidelined in the language provisions of the Constitution.

Gandhiji saw Hindustani as a bridge between communities. In October 1947, he stated: “This Hindustani should neither be Sanskritized Hindi nor Persianized Urdu but a happy combination of both […] To confine oneself exclusively to Hindi or Urdu would be a crime against intelligence and patriotism.” Rajaji (C Rajagopalachari) proposed writing Hindustani in regional scripts, while Minoo Masani and Hansa Mehta suggested Roman letters for wider accessibility. In 1945, Gandhi resigned from the Hindi Sahitya Sammelan when it insisted that only Hindi in the Nagari script could be the national language. To preserve national unity, India must return to Gandhiji’s vision of an inclusive ‘Rainbow Hindustani’ instead of pushing a rigid, Sanskritized version of Hindi.

The Folly of Anglophobia

The push to replace English with Hindi is another manifestation of linguistic chauvinism.

Hindi extremists in the Constituent Assembly vehemently opposed English, with Seth Govind Das declaring: “It is beyond our patience that because some of our brethren from Madras do not understand Hindustani, English should reign supreme in the Constituent Assembly.”

TT Krishnamachari, representing Madras, warned that ‘Hindi imperialism’ would only fuel separatist sentiments in South India. Maulana Abul Kalam Azad wisely pointed out that English had been the vital link uniting North and South India. “If today we give up English, then this linguistic relationship will cease to exist,” he cautioned.

In today’s AI-driven global economy, demoting English in favor of Hindi would be catastrophic for India’s youth. English proficiency provides access to education, employment, and international opportunities. India’s IT and outsourcing industries thrive because of the country’s strong English-language skills. AntiEnglish policies would not only weaken India’s global competitiveness but also exacerbate rural-urban disparities and deepen caste and class divisions.

Towards an Inclusive Language Policy

India needs a language policy that treats English on par with Hindi as recognizing English as an integral part of India’s linguistic landscape will ensure India’s global competitiveness. The policy must make Hindi more inclusive by incorporating words from Hindustani and regional languages, rather than enforcing a rigid Sanskritized version. Moreover. Regional languages must be given their due for ensuring that linguistic diversity is protected and promoted rather than suppressed.

Minority and tribal languages must be minded for safeguarding the rights of linguistic minorities and indigenous communities. Only by embracing linguistic pluralism can India truly achieve Vikasit Bharat @ 2047—an advanced, inclusive, and globally competitive nation.

(Faisal C.K. is Deputy Law Secretary to the Government of Kerala. Views are personal. Email: faisal.chelengara10@gmail.com)