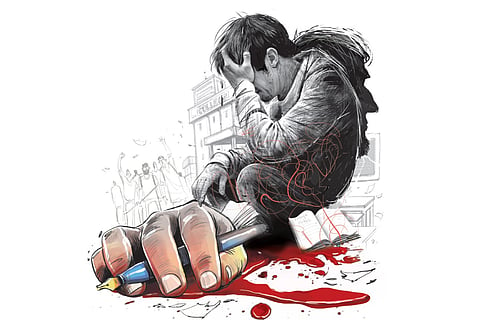

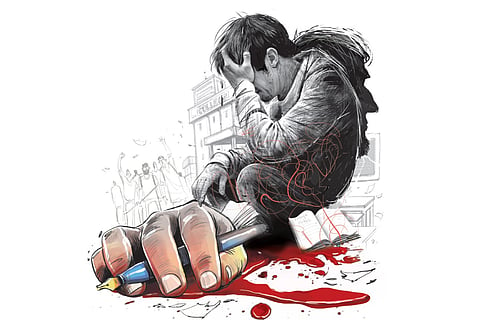

KOCHI: Mob trial. That was what allegedly took place at the College of Veterinary and Animal Sciences in Pookode, Wayanad, leading to the death of second-year student Sidharthan J S. Details of torture that Sidharthan suffered at the hands of his seniors and classmates are shocking, to say the least.

The 20-year-old was found dead in the hostel bathroom on February 18. Initially, the police thought it was a case of suicide. However, the post-mortem report and the police assessment painted a gruesome picture.

Sidharthan was brutally assaulted, paraded naked on the campus in front of around 130 students, beaten up allegedly with belts and iron rods. Reports say a glue gun, too, was used to torture him. He was also allegedly starved and denied water for three days.

Those accused, many of them members of the Students’ Federation of India (SFI), reportedly threatened other students against reporting the issue. It is alleged that Sidharthan was being ‘punished’ for misbehaving with a female senior.

According to the internal complaints committee (ICC) of the institute, the girl had filed a complaint against Sidharthan with the women’s cell. However, it was revealed later that the complaint was received a day after his death.

At least 18 students, including some local SFI leaders, have been named as accused in the case. Of the 31 students allegedly involved, 19 have been barred from taking admission in any educational institution in India for three years. Ten of them have been debarred for a year. And all students of the hostel have been suspended for failing to report the crime.

‘Mob lynching’

“It was mob lynching,” asserts retired High Court judge B Kemal Pasha.

“A warden was present at the hostel when the crime took place. It is said that the dean was aware. However, what I fail to understand is, why are the dean and that particular warden not arraigned in the case?”

If the authorities of an institution fail to report incidents of ragging they are liable to be prosecuted. “Strangely enough, here the police have not arraigned the dean (M K Narayanan) or that warden, who is a physical education teacher at the institution,” adds Justice Pasha.

As per the law, he points out, the students should have been immediately expelled and debarred from studying in any Indian institution for three years. “That was clearly not what happened initially,” he notes.

Justice Pasha argues that the key problem was that no one was ready to report or take action, not a failure of the law.

Notably, amid the startling developments in Sidharthanan’s case, another incident of assault by SFI members surfaced in Koyilandy, Kozhikode. A group of SFI members allegedly attacked C R Amal, a student of R Sankar Memorial SNDP Yogam Arts & Science College, on March 1.

Amal suffered serious injuries to his nose, and was taken to a hospital. He, however, was told to report it as a “motorcycle accident” to avoid repercussions. Later, he opened up about the assault at the insistence of his parents.

Ragging menace

“The lack of will to take effective action or even report the crime is not unique to one campus,” says Adv Sandhya Raju George, who has been part of anti-ragging cells in two colleges as an external member.

She recalls two cases that came across her during that period. “One was a sexual harassment case and the other ragging. In both cases, the internal members of the cells were reluctant to act, and waited for external members to make the crucial decisions.”

The reason is clear: “Fear.” In most colleges, especially government institutions, the students as well as teachers are reluctant to take action, especially if the culprits have political backing, Sandhya notes.

“This fear is the issue. The law is more than adequate if properly implemented. And that is where we fail,” she says.

“Go to any campus, you won’t find much details about anti-ragging mechanisms there. No banners, posters, etc. How will students know what to do in case they have to file a complaint?”

Sandhya believes the first step to be taken is to root out the fear factor. “Make sure the anti-ragging mechanism, the helpline number, etc, are visibly advertised on the campus properly. And importantly, cut off the outside involvement of political parties in campus affairs,” she adds.

Politics of ragging

RVG Menon, principal of Government College of Engineering, Kannur, believes ragging has continued despite stringent laws being in place.

Once, he adds, ragging was rather prevalent on professional college campuses in Kerala. “It is true that all student organisations, backed by political parties, had opposed ragging earlier. Not only student organisations but also progressive students themselves had argued against ragging since it is an antisocial activity and disgraces not only the victims but also the perpetrators,” he says.

However, Menon notes, the character of student organisations has changed since then. “More violence and intolerance are visible. Membership in organisations often becomes a cover for seeking power and dominance,” he says.

The days of the progressive students, who were socially responsible, becoming student leaders are a thing of the past, he feels.

“Quite often such students are targeted by the dominant groups. Meanwhile, students who are rough and violent get patronised,” says Menon.

“Socially committed students have gradually withdrawn. This unhealthy trend is responsible for the present situation.”

Menon believes there is only one effective solution: the political leadership has to recognise that this trend can mar not just student politics, but also politics in general.

“It is a law and order situation,” he says. “It shows the failure of the government. People will politicise judicial inquiry or committee reports, rather than finding solutions to help the students.”

Incidentally, the news about Sidharthanan’s death came out a couple of days after TNIE published a story on rising political violence at educational institutions, and asked experts as well as students if campus politics should be banned.

While most people were against a total ban, there were calls for reforms and effective mechanisms to prevent violence.

Poet and academician Prof Madhusudanan Nair stressed that students should be taught about cultural rapport, a sense of truth and justice. “If party politics function on campuses without these qualities, it spells disaster,” he said.

“Forums in educational institutions should not be stages for political parties to flaunt their strength. They should, rather, be moulded into what Swami Vivekananda envisaged: iron-willed men and women who will be protectors of society.”

Writer Khyrunnisa Vijayan also shared similar views. She noted that billing colleges as a party’s bastion was unhealthy. “That is not nice. Colleges should not be taken over by this kind of politics,” she said, stressing on the need for a democratic environment on campuses.